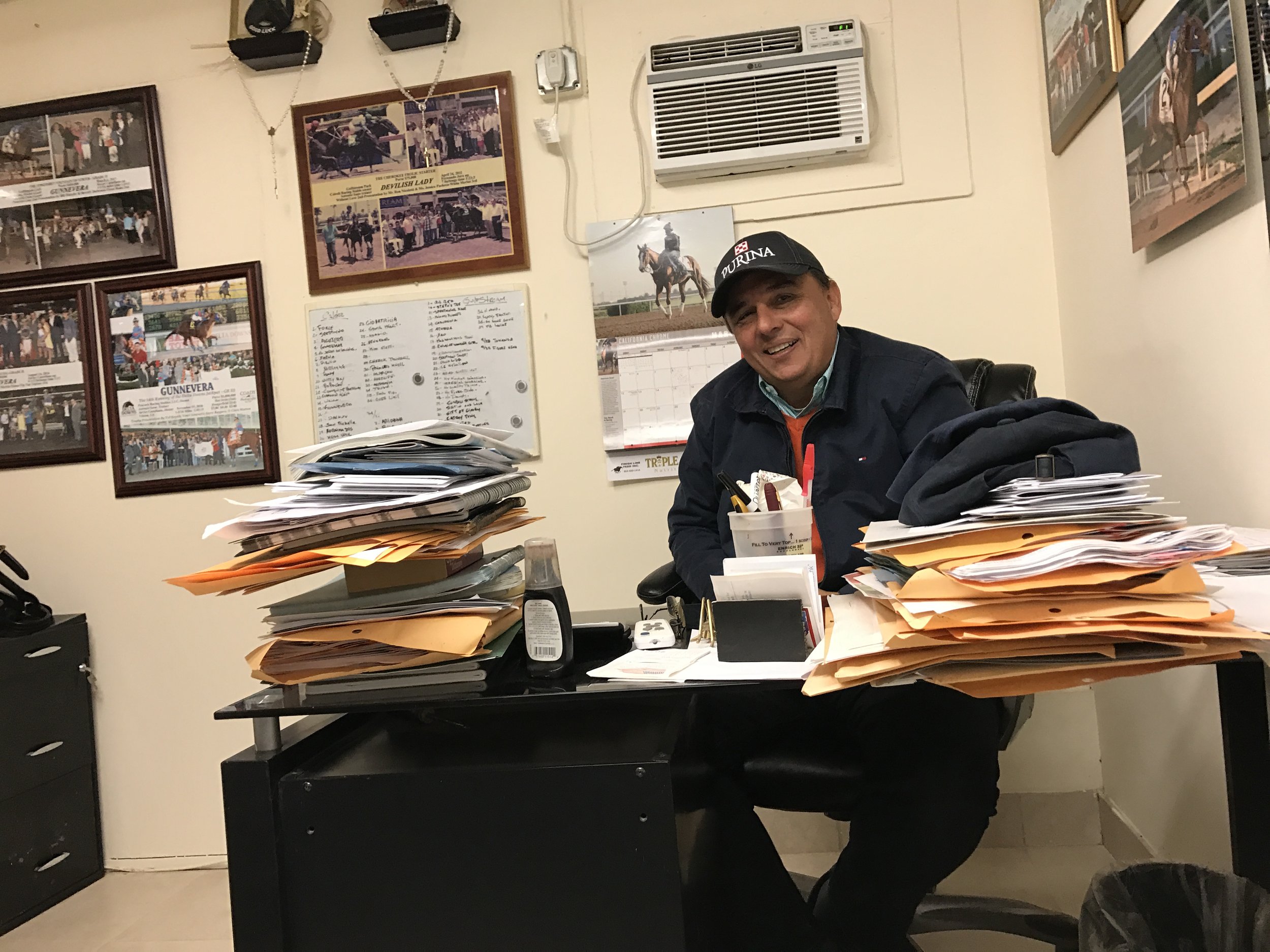

Whit Beckman trainer of Kentucky Derby contender - Honor Marie

/Article by Bill Heller

Trainer D. Whitworth Beckman grew up around horses but had never made the connection his parents did. His father, David, is a vet. His mother, Diane, rides and shows horses. “I was around them, but I wasn’t really interested, horses weren’t even on my radar.”

He spent two semesters at the College of Charleston. “I partied a lot,” he said. “I didn’t have any purpose. I was aimlessly floating around on alcohol. After two semesters, I figured I was wasting my time and wasting my parents’ money.”

His life got worse after dropping out from college. “I got pretty heavily involved with drinking. I hung out with a crew. A little wild. There was nothing that gave me purpose. I was a selfish kid.”

Eventually, he began helping his mom take care of polo horses and old show horses. And then he met his mom’s most difficult horse, a cantankerous Thoroughbred named Black Pearl. “I still have him,” his mother said. “We call him Blackie. He was a kook. He couldn’t be trained. He took off with his rider every morning, constantly switching leads. Whit taught himself how to ride on that horse.”

She still can’t believe it.

Beckman had found his purpose. “What I found with this horse was a new connection,“ he said. “He taught me a lot. You can lie and cheat with people. With a horse, it’s 100 percent honest. They do all the crap we ask them to do. They don’t lie or cheat. I think that’s refreshing. We should learn from them.”

He still is, and he doesn’t preclude learning from people, too. He worked for Todd Pletcher, Eion Harty and Chad Brown. Sandwiched in between, he trained in Saudi Arabia.

In 2023, only Beckman’s second full year on his own in the United States, he posted 13 victories, 13 seconds and four thirds in 102 starts with $1,468,695 in earnings, more than double what he earned the previous year. He recorded his first stakes victory and, soon afterwards, his first graded stakes. His stable grew from one horse to 26.

He had help, especially from his best friend Kristian Villante, a bloodstock agent who trades under the name of Legion Bloodstock. They became friends when they both worked for Todd Pletcher. “We have very similar personalities,” Villante said. “We became friends and it kind of grew.”

Villante helped Beckman grow his stable. “We said we’d give him the push,” Villante said. “You can open the door for someone, but then, it’s up to him what to do with it. You can provide the opportunity. A lot of credit to Whit.”

It’s been a journey. His mother said, “He doesn’t give up and he always shows up.”

“He didn’t get lucky,” Harty said. “He conducts himself in an exemplary fashion. He’s a good communicator. He’s a very good person. He inherited it from his family. I got to meet them a couple times. You can tell where he got it from.”

But his family didn’t see it coming.

“If you would have told me when he was in high school that he’d get up at 4:30 in the morning to take care of horses, I’d say you’re crazy,” recounted his father, David. “He’d go to a variety of farms with me and he didn’t seem to like it at all.”

His parents sure did. David and Diane Beckman met in a barn. “I was just out of college and I ran a barn in Goshen,” Diane said. “David came to the barn one day. He’s like Whit, very quiet. I thought he was very good-looking.”

David, who had just graduated from veterinary school in 1979, asked her to a University of Kentucky football game. They both went there.

Diane was smitten: “After a couple of months I said, `I want to marry him.’ His character … we’ve been married 42 years and I’ve never known anyone I respect more. He’s been a great father. He works every day. He’s kind. He was on call 24/7.”

The Beckman’s have four children. Whit is the oldest. “When the two boys would get in trouble and David wasn’t there, I’d say, `You’re going to go with your dad and work on weekends.’ I think that’s what turned Whit off on horses – for a while.”

Beckman explained, “She’d say you’re going to work with him. I associated being bad with horses.”

Whit seemed isolated growing up. “He struggled,” his mother said. “He was so shy. He was a kid who lived in his imagination. We sent him to college when he wasn’t ready for it. The College of Charleston put him in a hotel because the dorms were full. It wasn’t a good fit. He came home, and at that point he was really lost. He didn’t have the straight path in life. He met his struggles and has worked through them. Whit was a late bloomer.

“I have always been proud of the person Whit is. He’s trustworthy, and he’s always going to do the right thing, like his father. He’s never going to say anything unless he means it. He’s going to be honest. I’ve always been proud of him because he had the roughest road. He willed himself to where he is today.”

It took a decade and a half and many, many miles. After working with his mother’s horses, Beckman began working with Walter Binder at Churchill Downs and Louisiana Downs. Beckman returned to Kentucky in March, 2006, and his father helped him get a job with Alex Rankin at Up and Down Farm. “It was a great place to learn,” Beckman said. “It gave me a lot of experience. I developed horsemanship.”

He continued to develop that working with Dave Scanlon and Danny Montada getting Darley two-year-olds ready for sale at Keeneland.

Beckman was fortunate to meet trainer Eoin Harty, who reached out to Todd Pletcher for him. Later, Harty would hire Beckman to be his assistant.

Beckman began working for Pletcher at the 2007 Saratoga meeting. “Towards the end of the meet,” Beckman said. “You go to Kentucky. You see the routine. At that time, I could just wake up every morning and say, `How cool is this? I’m working for the top trainer in the country.’”

Pletcher was glad to have him: “He was always a very top-level assistant. Good horseman. Good demeanor around the barn. I’m not surprised to see him doing well.”

After working for Pletcher, Beckman journeyed to Saudi Arabia, an experience with mixed blessings. “At that point, I had just turned 30,” Beckman said. “It was an opportunity to go on my own. I thought it would be a cool thing to go to the Middle East. A rich tradition of horses. We won some races, but it was an extremely different environment. They bring you over, but they don’t listen. They say, `God’s will.’ Religion and their faith take precedence. It was sticky.”

In 2014, Beckman learned his girlfriend was pregnant. He returned to the U.S. and took a job with Harty. “He was already a qualified trainer by the time he got to me,” Harty said. “He was looking for a job and I was looking for an assistant. It worked out immediately. I showed him the way I like things to be done. He was a huge asset. He deserves nothing but the best.”

With a daughter on the way, Beckman returned to Saudi Arabia. He then returned to America to be there for her daughter Violette’s birth on December 23rd, 2015, three days after his 34th birthday. “When she was born, it was the best thing in my life,” he said.

Yet he was ready to return to Saudi Arabia a few days later. “I got to the jetway,” Beckman said. “I was standing there. I couldn’t do it. I was thinking of myself. I wanted to be home with my daughter. I turned around. I felt great about it.”

He felt even better when Charlie Boden, then with Darley, told him Chad Brown was looking for an assistant, as if Beckman was being rewarded for staying with his daughter.

Beckman began working with Brown on April 4th, 2016, and stayed until the summer of 2021 when he ventured on his own with the full support of his sister, Lindley Turner, who had been doing their fathers’ bookkeeping since 2008. Now she does both. “When Whit decided to train on his own, I offered to handle all the financial and the bookwork,” she said. “Not fun stuff, but necessary to keep the business going. Whit was away for 20 years. I wanted to see what he spent 20 years doing. It’s really cool to watch.”

She really liked what she saw from her brother: “He did all aspects of the job. He put a lot of time in everywhere. He had a very clear vision of what he wanted his stable to look like. As a money person, I said, `I believe in your vision.’ We put in basically everything a top barn would. He knew how he wanted to take care of his horses. How his shed row would look. He did the digging. He raked it out himself. From the very start, he put in the system he knew. He told me if you do this now, it will pay off. He was exactly right. It’s come to life, even though we started with one horse.”

She vividly remembers when that first horse, Truly Mischief, an unraced two-year-old owned and bred by Newtown Anner Stud, arrived, September 11th, 2021: “I remember the horse coming to me, and feeling bad for him because he was the only horse in the barn. I said, `We’re going to get you some buddies.’ It was really exciting, just watching Whit train his own horse. He’s very hands-on. It’s not a number thing with him. It’s about the individual.”

It always will be. “There are 20,000 Thoroughbreds bred every year,” Beckman said. “We have to do everything we can to make them reach their potential, no matter what level they’re at. Keep them happy; keep them healthy, get them fit to run. It’s funny, you constantly learn things. You show up every day. Get there early. Make the adjustments that have to happen for the individual. You’ve got to be passionate about it.”

His buddy Kristian Villante knew that he was: “I think he genuinely has a passion for it. It’s more than just a job. It’s a craft. There’s an art form that goes into racing. It’s not just the x’s and the o’s. There’s not really a playbook. What makes great trainers great trainers is they can make adjustments.”

Truly Mischief needed them. He was sixth in his debut, December 1st, 2021, then raced five more times before finally breaking his maiden at Horseshoe Indianapolis on September 28th, 2022, a year and 17 days after he arrived at Beckman’s barn. On February 26th, 2023, at Tampa Bay Downs, Truly Mischief finished fourth and was claimed for $25,000.

Beckman’s neighbor and friend at St. Xavier High School in Louisville, Chip Montgomery, sent Beckman his second horse, a two-year-old filly named Think Twice. She didn’t do much, finishing fifth in her debut, then seventh when claimed for $30,000.

Legion Racing’s four-year-old filly Sabalenka, Graham Grace Stable’s five-year-old gelding Harlan Estate and Ribble Farms’ three-year-old colt Honor Marie have been Beckman’s first three stars.

Sabalenka has two wins, two seconds and two thirds from nine starts with earnings of $427,498. She finished third in the 2023 Christiana Stakes at Delaware Park, July 15th, and second in the Dueling Grounds Oaks at Kentucky Downs, September 3rd. She is the most talented horse Valante helped him land. “They always had my back,” Beckman said. “She was the first one, as far as a nice horse, that gave me a little exposure. She was just a nice filly.”

In between those stakes placings, Harlan Estate, sent off at 37-1 in the $500,000 Tapit Stakes at Kentucky Downs, delivered Beckman’s first stakes victory – after surviving an inquiry. Far back in the field of 11 early, Harlan Estate won by a length and three-quarters under Declan Cannon. “The horse came from Canada, Beckman said. “We were looking for a turf horse who could compete in open company. She filled all the criteria. Everything blossomed. I knew we were on the right track. It was an awesome day.”

Also rallying from last in the field of eight, Honor Marie captured the $400,000 Grade 2 Kentucky Jockey Club Stakes by two lengths under Rafael Bejarano, earning 10 qualifying points for the 2024 Kentucky Derby. Honor Marie, a $40,000 purchase at the 2022 Keeneland September Yearling Sale, has two wins and a second in three career starts. “From the time he came in, he was a quality horse,” Beckman said. “He needed to mature on a physical level, but I knew I had a good horse in my hands. We knew two turns would help him. I wasn’t surprised, but it was awesome. We got to see what he did in the morning, materialize in the afternoon.”

Of course, he’s on the Kentucky Derby trail. His next start will be in the Grade 2 Risen Star Stakes at The Fair Grounds.

Beckman’s stable has grown to 26. His momentum is considerable. “I’m really proud of him,” Beckman’s father said. “He is my oldest child of four. He got a little lost. He’s overcome a lot. Horses saved his life.”

Villante’s father, Joe, who sells trainer products, is a big fan of Whit: “Whit is fantastic. He’s really good at communication and he doesn’t think he’s splitting the atom or inventing the game. I really appreciate that.”

He shared this: “About a year ago, we were at Tampa Bay and training horses were coming off the track. Whit had a low-level horse. He asked the rider what he saw the whole way back to the barn. He wrote all these notes. That’s attention to detail. It’s a moment that stuck in my head. I have friends for 20, 25 years. They don’t ask questions. They think they know everything. I was very impressed. This kid is going places.”

He already has. And he’s only just begun.