EIPH - could there be links to sudden death and pulmonary haemorrhage?

Dr Peter W. Physick-Sheard, BVSc, FRCVS, explores preliminary research and hypotheses, being conducted by the University of Guelph, to see if there is a possibility that these conditions are linked and what this could mean for future management and training of thoroughbreds.

"World's Your Oyster,” a three-year-old thoroughbred mare, presented at the veterinary hospital for clinical examination. She won her maiden start as a two-year-old and placed once in two subsequent starts. After training well as a three-year-old, she failed to finish her first start, easing at the top of the stretch, and was observed to fade abruptly during training. Some irregularity was suspected in heart rhythm after exercise. Thorough clinical examination, blood work, ultrasound of the heart and an ECG during rest and workout revealed nothing unusual.

Returning to training, Oyster placed in six of her subsequent eight starts, winning the last two. She subsequently died suddenly during early training as a four-year-old. At post-mortem, diagnoses of pulmonary haemorrhage and exercise-induced pulmonary haemorrhage were established—a very frustrating and unfortunate outcome.

Across the racing world, a case like this probably occurs daily. Anything that can limit a horse's ability to express its genetic potential is a major source of anxiety when training. The possibility of injury and lameness is the greatest concern, but a close second is respiratory disease, with bleeding from the lungs (most often referred to as exercise induced pulmonary [lung] haemorrhage or EIPH) being high on the list.

EIPH is thought to occur in as many as 85 percent of racehorses, and may initially be very mild without obvious clinical consequences. In some cases it can be associated with haemorrhage of sufficient severity for blood to appear at the nostrils, even at first occurrence. In many racing jurisdictions this is a potentially career-ending problem. In these horses, an impact on performance is unquestionable. Bleeding from the lungs is the reason for the existence of ‘Lasix programs,’ involving pre-race administration of a medication considered to reduce haemorrhage. Such programs are controversial—the justifications for their existence ranging from addressing welfare concerns for the horse to dealing with the performance impacts.

Much less frequently encountered is heavy exercise-associated bleeding from the nostrils (referred to as epistaxis), which can sometimes be accompanied by sudden death, during or shortly after exercise. Some horses bleed heavily internally and die without blood appearing at the nostrils. Haemorrhage may only become obvious when the horse is lying on its side, or not until post-mortem. Affected animals do not necessarily have any history of EIPH, either clinically or sub-clinically. There is an additional group of rare cases in which a horse simply dies suddenly, most often very soon after work and even after a winning performance, and in which little to nothing clearly explains the cause on post-mortem. This is despite the fact most racing jurisdictions study sudden death cases very closely.

EIPH is diagnosed most often by bronchoscopy—passing an endoscope into the lung after work and taking a look. In suspected but mild cases, there may not be sufficient haemorrhage to be visible, and a procedure called a bronchoalveolar lavage is performed. The airways are rinsed and fluid is collected and examined microscopically to identify signs of bleeding. Scoping to confirm diagnosis is usually a minimum requirement before a horse can be placed on a Lasix program.

Are EIPH, severe pulmonary haemorrhage and sudden death related? Are they the same or different conditions?

At the University of Guelph, we are working on the hypothesis that most often they are not different—that it’s degrees of the same condition, or closely related conditions perhaps with a common underlying cause. We see varying clinical signs as being essentially a reflection of severity and speed of onset of underlying problems.

Causes in individual cases may reflect multiple factors, so coming at the issues from several different directions, as is the case with the range of ongoing studies, is a good way to go so long as study subjects and cases are comparable and thoroughly documented. However, starting from the hypothesis that these may all represent basically the same clinical condition, we are approaching the problem from a clinical perspective, which is that cardiac dysfunction is the common cause.

Numerous cardiac disorders and cellular mechanisms have the potential to contribute to transient or complete pump (heart) failure. However, identifying them as potential disease candidates does not specifically identify the role they may have played, if any, in a case of heart failure and in lung haemorrhage; it only means that they are potential primary underlying triggers. It isn't possible for us to be right there when a haemorrhage event occurs, so almost invariably we are left looking at the outcome—the event of interest has passed. These concerns influence the approach we are taking.

Background

The superlative performance ability of a horse depends on many physical factors:

Huge ventilatory (ability to move air) and gas exchange capacity

Body structure including limb length and design - allows it to cover ground rapidly with a long stride

Metabolic adaptations - supports a high rate of energy production by burning oxygen, tolerance of severe metabolic disruptions toward the end of race-intensity effort

High cardiovascular capacity - allows the average horse to pump roughly a brimming bathtub of blood every minute

At race intensity effort, these mechanisms, and more, have to work in coordination to support performance. There is likely not much reserve left—two furlongs (400m) from the winning post—even in the best of horses. There are many wild cards, from how the horse is feeling on race day to how the race plays out; and in all horses there will be a ceiling to performance. That ceiling—the factor limiting performance—may differ from horse to horse and even from day to day. There’s no guarantee that in any particular competition circumstances will allow the horse to perform within its own limitations. One of these factors involves the left side of the heart, from which blood is driven around the body to the muscles.

A weak link - filling the left ventricle

The cardiovascular system of the horse exhibits features that help sustain a high cardiac output at peak effort. The feature of concern here is the high exercise pressure in the circulation from the right ventricle, through the lungs to the left ventricle. At intense effort and high heart rates, there is very little time available to fill the left ventricle—sometimes as little as 1/10 of a second; and if the chamber cannot fill properly, it cannot empty properly and cardiac output will fall. The circumstances required to achieve adequate filling include the readiness of the chamber to relax to accept blood—its ‘stiffness.’ Chamber stiffness increases greatly at exercise, and this stiffened chamber must relax rapidly in order to fill. That relaxation seems not to be sufficient on its own in the horse at high heart rates. Increased filling pressure from the circulation draining the lungs is also required. But there is a weak point: the pulmonary capillaries.

These are tiny vessels conducting blood across the lungs from the pulmonary artery to the pulmonary veins. During this transit, all the gas exchange needed to support exercise takes place. The physiology of other species tells us that the trained lung circulation achieves maximum flow (equivalent to cardiac output) by reducing resistance in those small vessels. This process effectively increases lung blood flow reserve by, among other things, dilating small vessels. Effectively, resistance to the flow of blood through the lungs is minimised. We know this occurs in horses as it does in other species; yet in the horse, blood pressure in the lungs still increases dramatically at exercise.

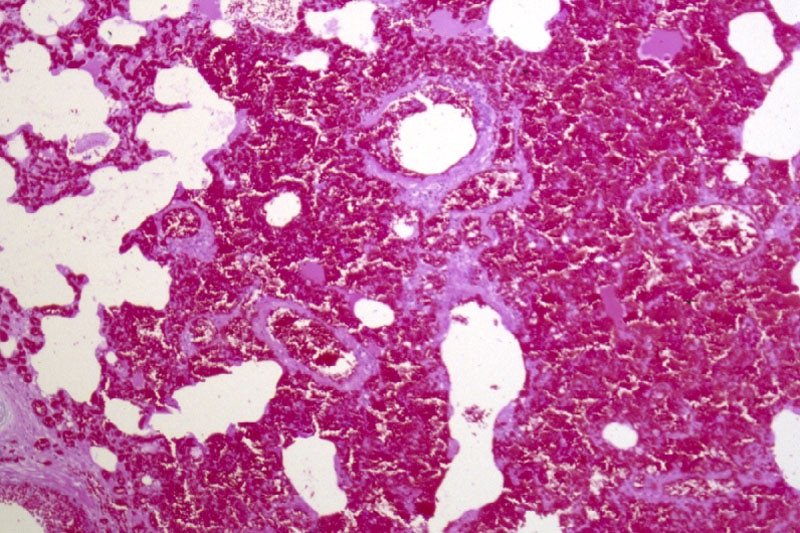

If this increase is not the result of resistance in the small vessels, it must reflect something else, and that appears to be resistance to flow into the left chamber. This means the entire lung circulation is exposed to the same pressures, including the thin-walled capillaries. Capillaries normally work at quite low pressure, but in the exercising horse, they must tolerate very high pressures. They have thin walls and little between them, and the air exchange sacs in the lung. This makes them vulnerable. It's not surprising they sometimes rupture, resulting in lung haemorrhage.

Recent studies identified changes in the structure of small veins through which the blood flows from the capillaries and on toward the left chamber. This was suspected to be a pathology and part of the long-term consequences of EIPH, or perhaps even part of the cause as the changes were first identified in EIPH cases. It could be, however, that remodelling is a normal response to the very high blood flow through the lungs—a way of increasing lung flow reserve, which is an important determinant of maximum rate of aerobic working.

The more lung flow reserve, the more cardiac output and the more aerobic work an animal can perform. The same vein changes have been observed in non-racing horses and horses without any history or signs of bleeding. They may even be an indication that everything is proceeding as required and a predictable consequence of intense aerobic training. On the other hand, they may be an indication in some horses that the rate of exercise blood flow through their lungs is a little more than they can tolerate, necessitating some restructuring. We have lots to learn on this point.

If the capacity to accommodate blood flow through the lungs is critical, and limiting, then anything that further compromises this process is likely to be of major importance. It starts to sound very much as though the horse has a design problem, but we shouldn't rush to judgement. Horses were probably not designed for the very intense and sustained effort we ask of them in a race. Real-world situations that would have driven their evolution would have required a sprint performance (to avoid ambush predators such as lions) or a prolonged slower-paced performance to evade predators such as wolves, with only the unlucky victim being pushed to the limit and not the entire herd.

Lung blood flow and pulmonary oedema

There is another important element to this story. High pressures in the capillaries in the lung will be associated with significant movement of fluid from the capillaries into lung tissue spaces. This movement in fact happens continuously at all levels of effort and throughout the body—it's a normal process. It's the reason the skin on your ankles ‘sticks’ to the underlying structures when you are standing for a long time. So long as you keep moving a little, the lymphatic system will draw away the fluid.

In a diseased lung, tissue fluid accumulation is referred to as pulmonary oedema, and its presence or absence has often been used to help characterise lung pathologies. The lung lymphatic system can be overwhelmed when tissue fluid is produced very rapidly. When a horse experiences sudden heart failure, such as when the supporting structures of a critical valve fail, one result is massive overproduction of lung tissue fluid and appearance of copious amounts of bloody fluid from the nostrils.

The increase in capillary pressure under these conditions is as great as at exercise, but the horse is at rest. So why is there no bloody fluid in the average, normal horse after a race? It’s because this system operates very efficiently at the high respiratory rates found during work: tissue fluid is pumped back into the circulation, and fluid does not accumulate. The fluid is pumped out as quickly as it is formed. An animal’s level of physical activity at the time problems develop can therefore make a profound difference to the clinical signs seen and to the pathology.

Usual events with unusual consequences

If filling the left ventricle and the ability of the lungs to accommodate high flow at exercise are limiting factors, surely this affects all horses. So why do we see such a wide range of clinical pictures, from normal to subclinical haemorrhage to sudden death?

Variation in contributing factors such as type of horse, type and intensity of work, sudden and unanticipated changes in work intensity, level of training in relation to work and the presence of disease states are all variables that could influence when and how clinical signs are seen, but there are other considerations.

Although we talk about heart rate as a fairly stable event, there is in fact quite a lot of variation from beat to beat. This is often referred to as heart rate variability. There has been a lot of work performed on the magnitude of this variability at rest and in response to various short-term disturbances and at light exercise in the horse, but not a lot at maximal exercise. Sustained heart rate can be very high in a strenuously working horse, with beats seeming to follow each other in a very consistent manner, but there is in fact still variation.

Some of this variation is normal and reflects the influence of factors such as respiration. However, other variations in rate can reflect changes in heart rhythm. Still other variations may not seem to change rhythm at all but may instead reflect the way electrical signals are being conducted through the heart.

These may be evident from the ECG but would not appear abnormal on a heart rate monitor or when listening. These variations, whether physiologic (normal) or a reflection of abnormal function, will have a presently, poorly understood influence on blood flow through the lungs and heart—and on cardiac filling. Influences may be minimal at low rates, but what happens at a heart rate over 200 and in an animal working at the limits of its capacity?

Normal electrical activation of the heart follows a pattern that results in an orderly sequence of heart muscle contraction, and that provides optimal emptying of the ventricles. Chamber relaxation complements this process.

An abnormal beat or abnormal interval can compromise filling and/or emptying of the left ventricle, leaving more blood to be discharged in the next cycle and back up through the lungs, raising pulmonary venous pressure. A sequence of abnormal beats can lead to a progressive backup of blood, and there may not be the capacity to hold it—even for one quarter of a second, a whole cardiac cycle at 240 beats per minute.

For a horse that has a history of bleeding and happens to be already functioning at a very marginal level, even minor disturbances in heart rhythm might therefore have an impact. Horses with airway disease or upper airway obstructions, such as roarers, might find themselves in a similar position. An animal that has not bled previously might bleed a little, one that has a history of bleeding may start again, or a chronic bleeder may worsen.

Relatively minor disturbances in cardiac function, therefore, might contribute to or even cause EIPH. If a horse is in relatively tough company or runs a hard race, this may also contribute to the onset or worsening of problems. Simply put, it's never a level playing field if you are running on the edge.

Severe bleeding

It has been suspected for many years that cases of horses dying suddenly at exercise represent sudden-onset cardiac dysfunction—most likely a rhythm disturbance. If the rhythm is disturbed, the closely linked and carefully orchestrated sequence of events that leads to filling of the left ventricle is also disturbed. A disturbance in cardiac electrical conduction would have a similar effect, such as one causing the two sides of the heart to fall out of step, even though the rhythm of the heart may seem normal.

The cases of horses that bleed profusely at exercise and even those that die suddenly without any post-mortem findings can be seen to follow naturally from this chain of events. If the changes in heart rhythm or conduction are sufficient, in some cases to cause massive pulmonary haemorrhage, they may be sufficient in other cases to cause collapse and death even before the horse has time to exhibit epistaxis or even clear evidence of bleeding into the lungs.

EIPH and dying suddenly

If these events are (sometimes) related, why is it that some horses that die of pulmonary haemorrhage with epistaxis do not show evidence of chronic EIPH? This is one of those $40,000 questions. It could be that young horses have had limited opportunity to develop chronic EIPH; it may be that we are wrong and the conditions are entirely unrelated. But it seems more likely that in these cases, the rhythm or conduction disturbance was sufficiently severe and/or rapid in onset to cause a precipitous fall in blood pressure with the animal passing out and dying rapidly.

In this interpretation of events, the missing link is the heart. There is no finite cutoff at which a case ceases to be EIPH and becomes pulmonary haemorrhage. Similarly, there is no distinct point at which any case ceases to be severe EIPH and becomes EAFPH (exercise-associated fatal pulmonary haemorrhage). In truth, there may simply be gradation obscured somewhat by variable definitions and examination protocols and interpretations.

The timing of death

It seems from the above that death should most likely take place during work, and it often does, but not always. It may occur at rest, after exercise. Death ought to occur more often in racing, but it doesn't.

The intensity of effort is only one factor in this hypothesis of acute cardiac or pump failure. We also have to consider factors such as when rhythm disturbances are most likely to occur (during recovery is a favourite time) and death during training is more often a problem than during a race.

A somewhat hidden ingredient in this equation is possibly the animal's level of emotional arousal, which is known to be a risk factor in humans for similar disturbances. There is evidence that emotions/psychological factors might be much more important in horses than previously considered. Going out for a workout might be more stimulating for a racehorse than a race because before a race, there is much more buildup and the horse has more time to adequately warm up psychologically. And then, of course, temperament also needs to be considered. These are yet further reasons that we have a great deal to learn.

Our strategy at the University of Guelph

These problems are something we cannot afford to tolerate, for numerous reasons—from perspectives of welfare and public perception to rider safety and economics. Our aim is to increase our understanding of cardiac contributions by identifying sensitive markers that will enable us to say with confidence whether cardiac dysfunction—basically transient or complete heart failure—has played a role in acute events.

We are also looking for evidence of compromised cardiac function in all horses, from those that appear normal and perform well, through those that experience haemorrhage, to those that die suddenly without apparent cause. Our hope is that we can not only identify horses at risk, but also focus further work on the role of the heart as well as the significance of specific mechanisms. And we hope to better understand possible cardiac contributions to EIPH in the process. This will involve digging deeply into some aspects of cellular function in the heart muscle, the myocardium of the horse, as well as studying ECG features that may provide insight and direction.

Fundraising is underway to generate seed money for matching fund proposals, and grant applications are in preparation for specific, targeted investigations. Our studies complement those being carried out in numerous, different centres around the world and hopefully will fill in further pieces of the puzzle. This is, indeed, a huge jigsaw, but we are proceeding on the basis that you can eat an elephant if you're prepared to process one bite at a time.

How can you help? Funding is an eternal issue. For all the money that is invested in horses there is a surprisingly limited contribution made to research and development—something that is a mainstay of virtually every other industry; and this is an industry.

Look carefully at the opportunities for you to make a contribution to research in your area. Consider supporting studies by making your experience, expertise and horses available for data collection and minimally invasive procedures such as blood sampling.

Connect with the researchers in your area and find out how you can help. Watch your horses closely and contemplate what they might be telling you—it's easy to start believing in ourselves and to stop asking questions. Keep meticulous records of events involving horses in your care— you never know when you may come across something highly significant. And work with researchers (which often includes track practitioners) to make your data available for study.

Remember that veterinarians and university faculty are bound by rules of confidentiality, which means what you tell them should never be ascribed to you or your horses and will only be used without any attribution, anonymously. And when researchers reach out to you to tell you what they have found and to get your reactions, consider actually attending the sessions and participating in the discussion; we can all benefit—especially the ultimate beneficiary which should be the horse. We all have lots to learn from each other, and finding answers to our many challenges is going to have to be a joint venture.

Finally, this article has been written for anybody involved in racing to understand, but covering material such as this for a broad audience is challenging. So, if there are still pieces that you find obscure, reach out for help in interpretation. The answers may be closer than you think!

Oyster

And what about Oyster? Her career was short. Perhaps, had we known precisely what was going on, we might have been able to treat her, or at least withdraw her from racing and avoid a death during work with all the associated dangers—especially to the rider and the associated welfare concerns.

Had we had the tools, we might have been able to confirm that whatever the underlying cause, she had cardiac problems and was perhaps predisposed to an early death during work. With all the other studies going on, and knowing the issue was cardiac, we might have been able to target her assessment to identify specific issues known to predispose.

In the future, greater insight and understanding might allow us to breed away from these issues and to better understand how we might accommodate individual variation among horses in our approaches to selection, preparation and competition. There might be a lot of Oysters out there!

For further information about the work being undertaken by the University of Guelph

Contact - Peter W. Physick-Sheard, BVSc, FRCVS.

Professor Emeritus, Ontario Veterinary College, University of Guelph - pphysick@uoguelph.ca

Research collaborators - Dr Glen Pyle, Professor, Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Guelph - gpyle@uoguelph.ca

Dr Amanda Avison, PhD Candidate, Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Guelph. ajowett@uoguelph.ca

References

Caswell, J.I. and Williams K.J. (2015), Respiratory System, In ed. Maxie, M. Grant, 3 vols., 6th edn., Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals, 2; London: Elsevier Health Sciences, 490-91.

Hinchcliff, KW, et al. (2015), Exercise induced pulmonary hemorrhage in horses: American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine consensus statement, J Vet Intern Med, 29 (3), 743-58.

Rocchigiani, G, et al. (2022), Pulmonary bleeding in racehorses: A gross, histologic, and ultrastructural comparison of exercise-induced pulmonary hemorrhage and exercise-associated fatal pulmonary hemorrhage, Vet Pathol, 16:3009858221117859. doi: 10.1177/03009858221117859. Online ahead of print.

Manohar, M. and T. E. Goetz (1999), Pulmonary vascular resistance of horses decreases with moderate exercise and remains unchanged as workload is increased to maximal exercise, Equine Vet. J., (Suppl.30), 117-21.

Vitalie, Faoro (2019), Pulmonary Vascular Reserve and Aerobic Exercise Capacity, in Interventional Pulmonology and Pulmonary Hypertension, Kevin, Forton (ed.), (Rijeka: IntechOpen), Ch. 5, 59-69.

Manohar, M. and T. E. Goetz (1999), Pulmonary vascular resistance of horses decreases with moderate exercise and remains unchanged as workload is increased to maximal exercise, Equine Vet. J., (Suppl.30), 117-21.

#Soundbites - With increased restrictions on the use of Lasix beginning this year, should tracks have protocols for horses’ environment in the barn concerning ventilation, air flow and bedding?

Compiled by Bill Heller

With increased restrictions on the use of Lasix beginning this year, should tracks have protocols for horses’ environment in the barn concerning ventilation, air flow and bedding?

Christophe Clement

It’s now a new thing. The environment is very important; I think about it every single day of my life because I think about my horses every single day of my life. Creating the best environment is very important. I’m a strong believer in fresh air. The more fresh air, the better. The more time you can keep them out of their stalls and grazing, the better. It shouldn’t be done by the tracks. Individuals should do it.

****************************************

Peter Miller

Peter Miller

It’s a horrible idea to begin with. Restricting Lasix is a horrible idea. That’s where I’m coming from. It doesn’t really matter what they do. Horses are going to always bleed without Lasix. It’s really environment. You can have the best barn in the world, the best ventilation, the best bedding; horses will still bleed without it. Those are all good practices. I use those practices with Lasix. You want clean air. You want all these things as part of animal husbandry. You want those things. But It’s a moot point without Lasix.

****************************************

Kenny McPeek

Kenny McPeek

Yes. I think it’s good that tracks maintain the proper environment. Enclosed ventilation in barns is bad for everybody, depending on what surface you’re on. There are open-air barns and racetracks which have poor environments. It’s very important. Horses need a clean environment.

****************************************

Ian Wilkes

It definitely would help. A closed environment is not natural for horses. You have to get them out, getting fresh air and grazing. With some tracks, there are no turnouts. There’s not a lot of room. I think it’s very important. It’s not good when you get away from horses living naturally and having nature take care of them. It gets dusty in barns with a closed environment. Even if you have the best bedding, if you pay the top dollar and you get this tremendous straw, when you shake it, it’s still dusty. Horses have allergies like people.

Ian Wilkes

****************************************

Jamie Ness

I think it’s very important. I think it really depends on where you are. At Delaware Park, they have open barns with a lot of ventilation. But that’s in the summer. I’m at Parx, just 50 miles away, in the winter time, and we have to keep the barn closed. It’s cold out there. It stays warm inside, but you have 40 horses in stalls with low ceilings. The ventilation isn’t that great.

****************************************

Gary Gullo

Gary Gullow

With or without Lasix, I believe good ventilation, bedding and good quality hay is the best thing for horses. Trainers need to have that. With dust and the environment, the daily stuff 24 hours a day, it definitely helps a horse to get good ventilation.

****************************************

Mitch Friedman

No. Absolutely not. The tracks have no idea what’s right or wrong. They’re making up rules as they go along. No Lasix. Yes Lasix. This is why the game changed. I worked horses for Hobeau (Farm). If a horse was hurt, they sent him back to the farm. Then they sent three other ones. Farms don’t exist anymore where they turn horses out. The more regulations and rules, it gets worse over the years. The problem is this, in my opinion. I was an assistant trainer for Gasper Moschera. He never had horses break down because they raced every month. Gasper would jog them. Now with Scoot Palmer, these races can’t be run because they’ll suffer breakdowns. The game was never like that. They keep coming up with rules that make it harder and harder.

****************************************

John Sadler

John Sadler

Yes. My experience is that better ventilation, more air, is really good at preventing airborne disease. Good ventilation is key. The one thing we try to do is eliminate dust in the barn. We ask our grooms to do it. Don’t fluff up their straw while they’re in the stall. Wait until they’re out to control the environment. Getting fresh air is very important.

*****************************************

With or without Lasix, I believe good ventilation, bedding and good quality hay is the best thing for horses. Trainers need to have that. With dust and the environment, the daily stuff 24 hours a day, it definitely helps a horse to get good ventilation.

****************************************

CLICK HERE to return to issue contents or sign up below to read this article in full

ISSUE 59 (PRINT)

$6.95

ISSUE 59 (DIGITAL)

$3.99

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Four issue subscription - ONLY $24.95

Life after Lasix

By Denise Steffanus

An estimated 95% of American racehorses go postward on Lasix, a diuretic that reduces bleeding in the lungs caused by extreme exertion. Now, nearly 50 years since horsemen and veterinarians battled for approval to use the therapeutic drug on race day, stakeholders in the industry have launched an initiative to phase out Lasix from American racing.

The debate whether Lasix, technically known as furosemide, is a performance enhancer or a performance enabler has raged for decades. With that debate comes the discussion whether Lasix helps the horse or harms it. But we’re not going to get into that debate here.

With racetrack conglomerates such as The Stronach Group and Churchill Downs adopting house rules to ban Lasix use on race day in two-year-olds starting this year and in stakes horses beginning 2021, the political football of a total Lasix ban for racing is headed to the end zone. Whether that total ban happens next year or in five years, racing needs to take an objective look at how this move will change the practices and complexion of the industry at large. The Lasix ban will affect more than what happens on the racetrack. Its tentacles will reach to the sales ring, the breeding shed, the betting window, and the owner’s pocket.

When Lasix first was approved for racing in 1974, only horses that visibly bled out the nostrils—an extreme symptom of exercise-induced pulmonary hemorrhage (EIPH)—were permitted to use the drug. A few years later, flexible endoscopes enabled veterinarians to identify horses with trace levels of EIPH internally that qualified them for Lasix. So many horses became approved for Lasix that most jurisdictions stopped requiring proof of EIPH to send a first-time starter postward on Lasix. All trainers had to do was declare it on the entry. Soon, nearly every horse was racing on Lasix, many with no proof it was needed. And that’s the situation we have today.

Racing regulations tag a horse as a bleeder only if it visibly hemorrhages from one or both nostrils (epistaxis). For this article, “bleeder” and “bleeding” are general terms for all horses with EIPH, not just overt bleeders. With almost every horse now competing on Lasix, no one knows how many horses actually need the drug to keep their lungs clear while racing. When Lasix is banned, we’ll find out.

Safety First

Racing Hall of Fame jockey Mike Smith

How a particular horse will react when capillaries in its lungs burst is unpredictable. Thoroughbreds are tough, so most horses will push through the trickle, and some may win despite it. Other horses may tire prematurely from diminished oxygen, which could cause them to take a bad step, bump another horse, or stumble. Fractious horses with more severe bleeding may panic when they feel choked of air. Will the current number of human and equine first-responders be adequate to handle the potential increase in these EIPH incidents?

Racing Hall of Fame rider Mike Smith, who earned two Eclipse Awards as outstanding jockey, has ridden in more than 33,000 races during his four decades on the track. He said he can feel a change in the horse under him if it begins to bleed.

“Honestly, a lot of times you just don’t see that ‘A’ effort that you normally would have seen out of the horse,” he said. “You know, they just don’t perform near as well because of the fact that they bled, which you find out later. … When they bleed enough, they can literally fall. It can happen. It’s dependent on how bad they bleed. If a horse bleeds real bad, they don’t get any oxygen. … I’ve been blessed enough to have pulled them up, and if I wouldn’t have, they probably would have gone down or died, one or the other, I guess. They’re few and far between when it’s that bad, but it does happen.

Dr. Tom Tobin

“If you literally see the blood, then you stop with them. You don’t continue because it’s very dangerous.”

In 2012, Dr. Tom Tobin, renowned pharmacologist at the University of Kentucky’s Maxwell Gluck Equine Research Center, and his colleagues reviewed the correlation between EIPH and acute/sudden death on the racetrack, as set forth in published research. They noted that 60%-80% of horses presumed to have died from a “heart attack” were found upon necropsy to have succumbed to hemorrhaging into the lungs. Tobin and his colleagues concluded their review with a warning: “EIPH-related acute/sudden death incidents have the potential to cause severe, including career-ending and potentially fatal injuries to jockeys and others riding these horses.”

Mark Casse has won 11 Sovereign Awards as Canada’s outstanding trainer, five Breeders’ Cups, and three Triple Crown races. He’s a member of the Horse Racing Hall of Fame in both Canada and the United States, one of just three individuals to accomplish that feat (Lucien Laurin and Roger Attfield are the others).

“If as soon as they ban Lasix, we start having more injuries, they’re going to have to do something about that,” Casse said. “It will be more than just first-responders. That’s pretty scary to think, ‘Ok, we’re going to take horses off Lasix, and so now we’re going to need more medical people out there.’ That doesn’t sound too good to me.”

Spring in the Air wins the 61st running of the Darley Alcibiades at Keeneland Racecourse.

Training Strategies

Casse has a special way of training horses with EIPH, but he was cagey about the details and reluctant to disclose his strategy.

“What I do is try to give any horse that I feel is a bleeder, especially four to five days into a race, a very light schedule,” he said. “That’s one of the main things I’ll do with my bad bleeders. So, in other words, not as much galloping or jogging—stuff like that.”

In 2018, trainer Ken McPeek had the most U.S. wins (19) without Lasix. Besides racing here, McPeek prepares a string of horses to race in Europe, where Lasix is not permitted on race day. He puts those horses on a lighter racing schedule.

“As long as a horse is eating well and doing well, their chances of bleeding are relatively small,” he said. “If a horse is fatigued and stressed, I always believed that would lead to bleeding.”

McPeek said if a two-year-old bleeds, the owner and trainer are going to have a long-term problem on their hands, and they’re better off not racing at two.

In 2012, the first year the Breeders’ Cup banned Lasix in two-year-olds, Casse’s rising star Spring in the Air entered the Grey Goose Juvenile Fillies (Gr1) fresh off an extraordinary effort in the Darley Alcibiades Stakes (Gr1), where she lagged behind in tenth then launched an explosive four-wide dash coming out of the turn to win by a length.

The filly had run all four prior races on Lasix, but without Lasix in the Juvenile Fillies, she never was better than fifth. After the race, Casse told reporters she bled.

“She went back on Lasix,” Casse said of Spring in the Air, who became Canada’s Champion 2-Year-Old Filly that same year.

Dr. Jeff Blea is a longtime racetrack veterinarian in California and a past president of the American Association of Equine Practitioners. He said racing without Lasix is going to require a substantial learning curve for trainers and their veterinarians. During this interview Blea was at Santa Anita Park, where he’s been working with trainers to figure out the best way to manage and train horses that race without Lasix.

“That’s a case-by-case discussion because all trainers have different routines and different programs,” he said. “In addition to the variability among trainers, you have individual horses that you have to factor into that conversation as well.”

When a horse comes off the track from a work or a race with severe EIPH, Blea asks the trainer if this has happened before or if it’s something new. If it’s new, he looks at the horse’s history for anything that could have precipitated it. Blea uses ultrasound and X-rays to examine the horse’s lungs.

“With ultrasound, I can often find where the bleed was,” he said. “If I X-ray the lungs, I’ll want to look for a lung lesion, which tells me it’s a chronic problem. I want to look at airway inflammation and the overall structure of the lungs. … I’ll wait a day and see if the horse develops a temperature. I’ll pull blood [work] because this bleed could be the nidus for a respiratory infection, and I want to be able to be ahead of it. I typically do not put horses on antibiotics if they suffer epistaxis, or bleed out the nose. Most times when I’ve had those, they don’t get sick, so I don’t typically prophylactically put them on antibiotics.

Based on his diagnostic workup, Blea will recommend that the horse walk the shed row for a week or not return to the track for a few weeks.

“Depending on the severity of my findings, the horse may need to be turned out,” he said. “I use inhalers quite a bit. I think those are useful for horses that tend to bleed. I’m a big fan of immune stimulants. I think those are helpful. Then just old-fashioned, take them off alfalfa, put them on shavings...things like that.”

Blea discusses air quality in the barn with the trainer—less dust, more open-air ventilation, and common sense measures to keep the environment as clean and healthy as possible.

Prominent owner Bill Casner and his trainer Eoin Harty began a program in January 2012 to wipe out EIPH in his racehorses. Casner's strategy to improve air quality for his horses and limit their exposure to disease is to power-wash stalls before moving into a shed row and fog them with ceragenins—a powerful, environmentally safe alternative to typical disinfectants. He has switched to peat moss bedding, which neutralizes ammonia, and he only feeds his horses hay that has been steamed to kill pathogens and remove particulates.

Particulate Mapping

Activities in barns, particularly during morning training hours, kick up a lot of dust. Researchers at Michigan State University looked at particulates (dust) that drift on the air in racetrack barns. Led by Dr. Melissa Millerick-May, the team sampled the air in barns and mapped the particulate concentration in a grid, documented the size of the particles, identified horses in those barns with airway inflammation and mucus, then correlated the incidence of airway disease with hot spots of airborne particulates.

Gulfstream Park has erected three “tent barns” that are large and airy with high ceilings and fans near the top.

For part of the 18-month study, the research team used hand-held devices to assess airborne particulates; another part outfitted the noseband of each horse's halter with a device that sampled the air quality in the horse's breathing zone.

Some stalls appeared to be chronic hot spots for particulates, and horses in those stalls chronically had excess mucus in their airways. Often, moving the horses out of those stalls solved the problem.

These hot spots were different for each barn. Interestingly, because small particulates lodge deep in the lungs more easily than large ones, a stall that visibly appears clear might be an invisible hot spot.

Getting Prepared for the Pegasus—Lasix-Free

Dr. Rob Holland is a former Kentucky racing commission veterinarian based in Lexington who consults on infectious disease and respiratory issues, for which he obtained a PhD. Months prior to the Lasix-free Pegasus World Cup Invitational Stakes at Gulfstream Park in Florida, several trainers asked his advice on how to condition their horses so they could compete without Lasix. He told them they needed to start the program at least six weeks before the race. His first recommendation was to use ultrasound on the horse’s lungs to make sure they didn’t have scarring, which is a factor in EIPH, because scar tissue doesn’t stretch, it rips. Scarring can develop from a prior respiratory infection, such as pneumonia, or repeated episodes of EIPH. Next Holland directed the trainers to have the horse’s upper airway scoped for inflammation and excess mucus.

“I had one trainer who scoped the horse’s upper airway and trachea and decided, with the history of the horse, against running in the race without Lasix,” Holland said. “So there were trainers who were really on the fence, and that was for the betterment of the horse. Every trainer I talked to, that was their main focus: How do I do this so that my horse is OK? That was always the first question they would ask me. Second, they would ask me if I could guarantee [that] running their horse without Lasix wouldn’t cause a problem, and the answer is there’s no guarantee.”

Holland instructed trainers to start cleaning up the horse’s environment at least six weeks before the race to rid the air of dust, allergens and mold. He told them not to store hay and straw above the stalls; remove the horse from the barn while cleaning stalls and shaking out bedding; don’t use leaf blowers to clean the shed row; don’t set large fans on the ground in the shed row; elevate them so they don’t stir up dust; practice good biosecurity to avoid spreading disease; and steam or soak the horse’s hay and feed it on the ground. All this reduces irritation and inflammation in the airway.

The Pegasus World Cup Invitational at Gulfstream Park, 2020.

Holland prescribed nebulizing the horse’s lungs twice a day either with a chelated silver solution that kills microorganisms or ordinary saline solution to soothe the airway. He cautioned trainers with allergic horses not to use immunostimulants, which might cause adverse reactions in them.

By starting the program well in advance of the race, trainers were able to experiment with management and training strategies to see which worked best.

“We programmed all the horses to be ready for a race without Lasix by starting the program at least a month before the race,” Holland said. “We tried to simulate the exact situation they’d be going into at Gulfstream—same bedding, same feed, same hay, but no meds. If the horses didn’t have a problem, they could give their best. Also, I wanted the trainers to test the theory that the horse could do OK in a work without Lasix. So the horses all worked and got scoped afterward to see that there weren’t any issues before the Pegasus. The trainers followed my advice, and they knew their horses would be OK. And they were.”

Confidentiality prohibited Holland from identifying the trainers who consulted him, but he said all their horses ran competitively in the Pegasus with only trace amounts of bleeding or none at all.

Help Us, Please

Some horsemen have expressed frustration, complaining that racetracks are telling them they have to race without Lasix …

CLICK HERE to return to issue contents

ISSUE 57 (PRINT)

$6.95

ISSUE 57 (DIGITAL) -

$3.99

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Four issue subscription - ONLY $24.95

Sid Fernando - The thought-provoking

By Giles Anderson

I can’t quite believe that it’s just over six years since Sid Fernando first wrote his quarterly column for North American Trainer. The Triple Crown 2018 issue (number 49) was his last with us, and his regular thoughts can now be found in a bi-monthly column in the excellent Thoroughbred Daily News.

But, before we unveil our new columnist in our “Breeders’ Cup” / Fall issue later this year, I thought it would be interesting to read through the Sid’s old columns here and pick out two to revisit. With 25 to choose from, narrowing the list down has certainly proven to be a tough choice!

Sid’s first column was published in our Triple Crown 2012 issue (24) under the headline of “Scratching beneath the surface of the injury debate.” This was at the time when the New York Times and writer Joe Drape were at their most vociferous about racing, drug issues, and a correlation between breakdowns on track. In the column, The Jockey Club’s president and CEO James L. Gagliano was quoted (New York Times) as saying that “The Jockey Club continues to believe that horses should run only when they are free from the influence of medication and that there should be no place in this sport for those who repeatedly violate medication rules.”

I’m sure that the powers that be will continue to beat the same drum, and they are right to do so. But six years on, it would be fair to say that we’ve become far more aware of those who violate rules on multiple occasions, and perhaps the industry as a whole isn’t as tolerant as it was six years ago towards the minority of trainers who do flout the rules.

But in all this time, have we made up enough ground to educate the wider public on what is acceptable for the purpose of medicating animals as opposed to drugs with the intent of enhancing performance?

Sid’s article also included analysis from studies conducted by the now defunct Thoroughbred Times, which clearly showed how the risk to injury / “incident” rate was greatly reduced when horses ran on a synthetic surface compared to a conventional dirt surface.

Over the past couple of years, I’ve seen an updated variation of the same analysis, and indeed the trend is still there. It’s just a shame that synthetic surfaces seem to have fallen somewhat out of fashion.

Fast forward to the August -- October 2015 issue (37), where Sid came up with what, for me, was one of his most thought provoking columns. It first appeared in 2015, just after we had our first Triple Crown winner in 37 years. In his column, Sid compared the state of the wagering industry in Affirmed’s Triple Crown-winning year of 1978 against 2015, American Pharoah’s year.

The key points of the column are succinctly covered in the following four paragraphs:

If 1978 was a watershed year until American Pharoah in 2015, consider this about the 1970s: It was also a time when racetrack handle funded purses and the pari-mutuel tax was the major gambling revenue generator for state governments. In stark contrast, this isn't the case today.

Truth be told, under the nostalgic gold-plating of the 1970s, there were chinks in its armor that are gaping holes now. It was, for instance, the era when Lasix was legally introduced, and what a lightning rod for controversy that's become now. More significantly, though, it was the era of the Interstate Horse Racing Act (IHA) of 1978, a piece of federal legislation enacted to address on-track pari-mutuel declines -- big signs of future trouble -- as technology spawned the growing phenomenon of simulcast wagering and the growth of Advance Deposit Wagering (ADW) platforms across state lines.

Between 1978 and 2015, a Trojan horse -- the racino -- entered the game as state governments looked for other opportunities to boost coffers. And like a "pusher" in a 1970s playground, the racino hooked racing, already weakened through years of neglect and relegated to the fringe from the mainstream as a "niche" game, by giving it a taste of huge purses from gaming monies. Horsemen got sky high, but at what price? The deal was done in party with state governments in exchange for expanded gaming that competes with racing's core product, gambling. And that gaming money is now funding purses at racinos, and racing is as dependent on it as a junkie on dope.

Ultimately, the only way to organically grow the game is through an increase in pari-mutuel wagering, and one way to do that is to make betting on horses as attractive as other forms of gaming. At present, the takeout is too high to compete, and this is an issue that racing's leaders must address with the same zeal they address Lasix and other matters. There's still some $10 billion bet on racing per year, but this game doesn't have the legs to last another 37 years in its current state.

With the coming of age for sports betting in 2018, the sentiment of this piece perhaps rings more true today than it did three years ago.

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD -

August - October 2018, issue 49 (PRINT)

$5.95

August - October 2018, issue 49 (DOWNLOAD)

$3.99

Why not subscribe?

Don't miss out and subscribe to receive the next four issues!

Print & Online Subscription

$24.95

Sid Fernando - The Lasix anomaly

Sid Fernando talks about how Wesley Ward's successful raids on the elite European race meetings goes in some way to dispel the myth that Lasix is a performance enhancer. Time after time Ward sends out winners in Europe at meetings such as Royal Ascot but with Lasix being a banned substance it shows that maybe there is too much faith put into the drug in America.

Sid Fernando - no lie, no link (yet) between lasix and breakdowns

CLICK ON IMAGE TO READ ARTICLE

North American Trainer (Issue 26 - Fall 2012)

![Life After LasixWords: Denise SteffanusAn estimated 95% of American racehorses go postward on Lasix, a diuretic that reduces bleeding in the lungs caused by extreme exertion. Now, nearly 50 years since horsemen and veterinarians battled for approval to use the therapeutic drug on race day, stakeholders in the industry have launched an initiative to phase out Lasix from American racing.The debate whether Lasix, technically known as furosemide, is a performance enhancer or a performance enabler has raged for decades. With that debate comes the discussion whether Lasix helps the horse or harms it. But we’re not going to get into that debate here.With racetrack conglomerates such as The Stronach Group and Churchill Downs adopting house rules to ban Lasix use on race day in two-year-olds starting this year and in stakes horses beginning 2021, the political football of a total Lasix ban for racing is headed to the end zone. Whether that total ban happens next year or in five years, racing needs to take an objective look at how this move will change the practices and complexion of the industry at large. The Lasix ban will affect more than what happens on the racetrack. Its tentacles will reach to the sales ring, the breeding shed, the betting window, and the owner’s pocket.When Lasix first was approved for racing in 1974, only horses that visibly bled out the nostrils—an extreme symptom of exercise-induced pulmonary hemorrhage (EIPH)—were permitted to use the drug. A few years later, flexible endoscopes enabled veterinarians to identify horses with trace levels of EIPH internally that qualified them for Lasix. So many horses became approved for Lasix that most jurisdictions stopped requiring proof of EIPH to send a first-time starter postward on Lasix. All trainers had to do was declare it on the entry. Soon, nearly every horse was racing on Lasix, many with no proof it was needed. And that’s the situation we have today.Racing regulations tag a horse as a bleeder only if it visibly hemorrhages from one or both nostrils (epistaxis). For this article, “bleeder” and “bleeding” are general terms for all horses with EIPH, not just overt bleeders. With almost every horse now competing on Lasix, no one knows how many horses actually need the drug to keep their lungs clear while racing. When Lasix is banned, we’ll find out.Safety FirstHow a particular horse will react when capillaries in its lungs burst is unpredictable. Thoroughbreds are tough, so most horses will push through the trickle, and some may win despite it. Other horses may tire prematurely from diminished oxygen, which could cause them to take a bad step, bump another horse, or stumble. Fractious horses with more severe bleeding may panic when they feel choked of air. Will the current number of human and equine first-responders be adequate to handle the potential increase in these EIPH incidents?Racing Hall of Fame rider Mike Smith, who earned two Eclipse Awards as outstanding jockey, has ridden in more than 33,000 races during his four decades on the track. He said he can feel a change in the horse under him if it begins to bleed.“Honestly, a lot of times you just don’t see that ‘A’ effort that you normally would have seen out of the horse,” he said. “You know, they just don’t perform near as well because of the fact that they bled, which you find out later. … When they bleed enough, they can literally fall. It can happen. It’s dependent on how bad they bleed. If a horse bleeds real bad, they don’t get any oxygen. … I’ve been blessed enough to have pulled them up, and if I wouldn’t have, they probably would have gone down or died, one or the other, I guess. They’re few and far between when it’s that bad, but it does happen.“If you literally see the blood, then you stop with them. You don’t continue because it’s very dangerous.”In 2012, Dr. Tom Tobin, renowned pharmacologist at the University of Kentucky’s Maxwell Gluck Equine Research Center, and his colleagues reviewed the correlation between EIPH and acute/sudden death on the racetrack, as set forth in published research. They noted that 60%-80% of horses presumed to have died from a “heart attack” were found upon necropsy to have succumbed to hemorrhaging into the lungs. Tobin and his colleagues concluded their review with a warning: “EIPH-related acute/sudden death incidents have the potential to cause severe, including career-ending and potentially fatal injuries to jockeys and others riding these horses.”Mark Casse has won 11 Sovereign Awards as Canada’s outstanding trainer, five Breeders’ Cups, and three Triple Crown races. He’s a member of the Horse Racing Hall of Fame in both Canada and the United States, one of just three individuals to accomplish that feat (Lucien Laurin and Roger Attfield are the others).“If as soon as they ban Lasix, we start having more injuries, they’re going to have to do something about that,” Casse said. “It will be more than just first-responders. That’s pretty scary to think, ‘Ok, we’re going to take horses off Lasix, and so now we’re going to need more medical people out there.’ That doesn’t sound too good to me.”Training StrategiesCasse has a special way of training horses with EIPH, but he was cagey about the details and reluctant to disclose his strategy.“What I do is try to give any horse that I feel is a bleeder, especially four to five days into a race, a very light schedule,” he said. “That’s one of the main things I’ll do with my bad bleeders. So, in other words, not as much galloping or jogging—stuff like that.”In 2018, trainer Ken McPeek had the most U.S. wins (19) without Lasix. Besides racing here, McPeek prepares a string of horses to race in Europe, where Lasix is not permitted on race day. He puts those horses on a lighter racing schedule.“As long as a horse is eating well and doing well, their chances of bleeding are relatively small,” he said. “If a horse is fatigued and stressed, I always believed that would lead to bleeding.”McPeek said if a two-year-old bleeds, the owner and trainer are going to have a long-term problem on their hands, and they’re better off not racing at two.In 2012, the first year the Breeders’ Cup banned Lasix in two-year-olds, Casse’s rising star Spring in the Air entered the Grey Goose Juvenile Fillies (Gr1) fresh off an extraordinary effort in the Darley Alcibiades Stakes (Gr1), where she lagged behind in tenth then launched an explosive four-wide dash coming out of the turn to win by a length.The filly had run all four prior races on Lasix, but without Lasix in the Juvenile Fillies, she never was better than fifth. After the race, Casse told reporters she bled.“She went back on Lasix,” Casse said of Spring in the Air, who became Canada’s Champion 2-Year-Old Filly that same year.Dr. Jeff Blea is a longtime racetrack veterinarian in California and a past president of the American Association of Equine Practitioners. He said racing without Lasix is going to require a substantial learning curve for trainers and their veterinarians. During this interview Blea was at Santa Anita Park, where he’s been working with trainers to figure out the best way to manage and train horses that race without Lasix.“That’s a case-by-case discussion because all trainers have different routines and different programs,” he said. “In addition to the variability among trainers, you have individual horses that you have to factor into that conversation as well.”When a horse comes off the track from a work or a race with severe EIPH, Blea asks the trainer if this has happened before or if it’s something new. If it’s new, he looks at the horse’s history for anything that could have precipitated it. Blea uses ultrasound and X-rays to examine the horse’s lungs.“With ultrasound, I can often find where the bleed was,” he said. “If I X-ray the lungs, I’ll want to look for a lung lesion, which tells me it’s a chronic problem. I want to look at airway inflammation and the overall structure of the lungs. … I’ll wait a day and see if the horse develops a temperature. I’ll pull blood [work] because this bleed could be the nidus for a respiratory infection, and I want to be able to be ahead of it. I typically do not put horses on antibiotics if they suffer epistaxis, or bleed out the nose. Most times when I’ve had those, they don’t get sick, so I don’t typically prophylactically put them on antibiotics.”Based on his diagnostic workup, Blea will recommend that the horse walk the shed row for a week or not return to the track for a few weeks.“Depending on the severity of my findings, the horse may need to be turned out,” he said. “I use inhalers quite a bit. I think those are useful for horses that tend to bleed. I’m a big fan of immune stimulants. I think those are helpful. Then just old-fashioned, take them off alfalfa, put them on shavings...things like that.”Blea discusses air quality in the barn with the trainer—less dust, more open-air ventilation, and common sense measures to keep the environment as clean and healthy as possible.Prominent owner Bill Casner and his trainer Eoin Harty began a program in January 2012 to wipe out EIPH in his racehorses. Casner's strategy to improve air quality for his horses and limit their exposure to disease is to power-wash stalls before moving into a shed row and fog them with ceragenins—a powerful, environmentally safe alternative to typical disinfectants. He has switched to peat moss bedding, which neutralizes ammonia, and he only feeds his horses hay that has been steamed to kill pathogens and remove particulates.Particulate MappingActivities in barns, particularly during morning training hours, kick up a lot of dust. Researchers at Michigan State University looked at particulates (dust) that drift on the air in racetrack barns. Led by Dr. Melissa Millerick-May, the team sampled the air in barns and mapped the particulate concentration in a grid, documented the size of the particles, identified horses in those barns with airway inflammation and mucus, then correlated the incidence of airway disease with hot spots of airborne particulates.For part of the 18-month study, the research team used hand-held devices to assess airborne particulates; another part outfitted the noseband of each horse's halter with a device that sampled the air quality in the horse's breathing zone.Some stalls appeared to be chronic hot spots for particulates, and horses in those stalls chronically had excess mucus in their airways. Often, moving the horses out of those stalls solved the problem.These hot spots were different for each barn. Interestingly, because small particulates lodge deep in the lungs more easily than large ones, a stall that visibly appears clear might be an invisible hot spot.Getting Prepared for the Pegasus—Lasix-FreeDr. Rob Holland is a former Kentucky racing commission veterinarian based in Lexington who consults on infectious disease and respiratory issues, for which he obtained a PhD. Months prior to the Lasix-free Pegasus World Cup Invitational Stakes at Gulfstream Park in Florida, several trainers asked his advice on how to condition their horses so they could compete without Lasix. He told them they needed to start the program at least six weeks before the race. His first recommendation was to use ultrasound on the horse’s lungs to make sure they didn’t have scarring, which is a factor in EIPH, because scar tissue doesn’t stretch, it rips. Scarring can develop from a prior respiratory infection, such as pneumonia, or repeated episodes of EIPH. Next Holland directed the trainers to have the horse’s upper airway scoped for inflammation and excess mucus.“I had one trainer who scoped the horse’s upper airway and trachea and decided, with the history of the horse, against running in the race without Lasix,” Holland said. “So there were trainers who were really on the fence, and that was for the betterment of the horse. Every trainer I talked to, that was their main focus: How do I do this so that my horse is OK? That was always the first question they would ask me. Second, they would ask me if I could guarantee [that] running their horse without Lasix wouldn’t cause a problem, and the answer is there’s no guarantee.”Holland instructed trainers to start cleaning up the horse’s environment at least six weeks before the race to rid the air of dust, allergens and mold. He told them not to store hay and straw above the stalls; remove the horse from the barn while cleaning stalls and shaking out bedding; don’t use leaf blowers to clean the shed row; don’t set large fans on the ground in the shed row; elevate them so they don’t stir up dust; practice good biosecurity to avoid spreading disease; and steam or soak the horse’s hay and feed it on the ground. All this reduces irritation and inflammation in the airway.Holland prescribed nebulizing the horse’s lungs twice a day either with a chelated silver solution that kills microorganisms or ordinary saline solution to soothe the airway. He cautioned trainers with allergic horses not to use immunostimulants, which might cause adverse reactions in them.By starting the program well in advance of the race, trainers were able to experiment with management and training strategies to see which worked best.“We programmed all the horses to be ready for a race without Lasix by starting the program at least a month before the race,” Holland said. “We tried to simulate the exact situation they’d be going into at Gulfstream—same bedding, same feed, same hay, but no meds. If the horses didn’t have a problem, they could give their best. Also, I wanted the trainers to test the theory that the horse could do OK in a work without Lasix. So the horses all worked and got scoped afterward to see that there weren’t any issues before the Pegasus. The trainers followed my advice, and they knew their horses would be OK. And they were.”Confidentiality prohibited Holland from identifying the trainers who consulted him, but he said all their horses ran competitively in the Pegasus with only trace amounts of bleeding or none at all.Help Us, PleaseSome horsemen have expressed frustration, complaining that racetracks are telling them they have to race without Lasix, but they’re not telling them how to accomplish this or helping them implement the change. Continuing education focuses mostly on reducing breakdowns, but it offers no modules to help trainers understand and deal with EIPH—arguably the hottest topic in racing.Just prior to the Pegasus in January, The Stronach Group rolled out its new brand, 1/ST Racing, and named Craig Fravel its chief executive officer. His task is to manage and oversee racing operations at all Stronach Group-owned racetracks and training centers. Fravel came to 1/ST (pronounced “First”) after serving eight years as CEO of the Breeders’ Cup.Fravel said he wasn’t aware of the horsemen’s frustration.“I’m happy to jump into that and make sure that our communication with them in terms of best practices and concepts is addressed,” he said, vowing to have Dr. Rick Arthur, equine medical director for the California Horse Racing Board who helped develop the Jockey Club’s continuing education modules, look into adding information about EIPH and racing without Lasix.Fravel also wants horsemen to know that 1/ST is dedicated to improving air quality on the backside.“Ventilation and dust control is a big part of eventually weaning the horse population from Lasix, and we’re certainly willing to look at that and figure out ways we can improve the overall ventilation and conditions for the horses,” he said.Fravel voiced an interest in Michigan State’s particulate mapping and said he planned to follow up with Dr. Millerick-May.Gulfstream Park has erected three “tent barns” that are large and airy with high ceilings and fans near the top. At Palm Meadows Training Center about 40 miles from Gulfstream, plans include building tent barns to house 300-400 new stalls.“The one thing about Florida racing is that all our barns are basically open,” said Mike Lakow, vice president of racing for Gulfstream Park. “It’s not enclosed barns as in the Northeast where weather is an issue.”Fravel said the same of Santa Anita’s barns.“They’re in a nice, breezy environment where much of the barn area is much more outdoor oriented than you would find on the East Coast,” he said. “Then at Laurel [Park in Maryland] we also have long-term plans for the entire barn area, which should be completed—if the current planning continues to take effect—in roughly two years’ time.”So Far, So GoodWithout knowing how many horses will be able to race competitively without Lasix and how many will be lost through attrition because their owners decide to stop on them, filling races and field size becomes a question. Lakow said this hasn’t been an issue so far.“As far as our two-year-old races at Gulfstream Park this year, we’ve had close to 25 without Lasix, and field size has not diminished at all,” he said going into the 4th of July weekend. “…With the Stronach Group deciding to run our two biggest races, the Pegasus World Cup and the Pegasus World Cup Turf in January without Lasix, we had full fields, and I really didn’t hear issues of horses bleeding from those two races.“Now, granted, we invited every top dirt horse and turf horse in the country, and I would say less than 5% said they couldn’t participate because there was no Lasix.”(NOTE: The California Horse Racing Board and Churchill Downs were given the opportunity to speak to horsemen through this article but declined. The New York Racing Association did not respond.)Handicapping: No More Speed in a BottleA first-time Lasix horse always has been the bettors’ Golden Ticket, especially when it was inside information not printed in the program. For decades, astute handicappers have studied how individual horses react when racing on Lasix or without it. That’s all about to change.Paul Matties Jr., who earned the 2016 Eclipse Award for handicapping, calls Lasix “speed in a bottle,” and he knows most people are going to take that the wrong way. Matties believes a horse keeps itself together better when it races on Lasix, giving the jockey instant speed at his fingertips.“It’s more of a sustained run,” Matties said. “They’re going to have to work more for it instead of just asking. Modern jockeys have been used to this. I ask and the horse will give it to me because it’s speed in a bottle. It’s canned speed. And I believe a lot of that is because of Lasix.“Jockeys nowadays know they have it, so it’s more about relaxing the horse and getting into a rhythm. They don’t have to worry about the speed part. I think as they get off Lasix, they’re going to have to worry about that more. It is going to be different, and I think the jockeys will notice the difference.“As far as handicapping, the one thing that definitely is going to happen in dirt races is that speed will do better. It’s going to go against what people think in general. But I think the horses that don’t get the lead will be the ones that will bleed more. I don’t think it will happen every race, obviously. But, in general, I think speed will do a little bit better. I think the Lasix keeps the horses together longer, where they’re able to sit chilly as long as they can and have an explosive run. They will have less of that ability to do that. I will definitely look for horses near to the lead.”Buyers, Sellers and BreedersBloodstock agent Gayle Van Lear believes EIPH could become an undesirable trait that buyers and breeders will avoid. Horsemen will need to start paying attention to those horses racing now to see if they perform poorly when they don’t receive Lasix. Then they will have to decide if they want to breed to them when they retire from racing. In the not-so-distant future, will certain bloodlines fizzle out on the track because they inherited a predisposition to EIPH?“That’s like anything that falls on the same line, like all the Storm Cats that had offset knees and all the crooked Mr. Prospectors,” Van Lear said. “Those, over time, phase themselves out through the gene pool, and the chips fall where they fall. So I don’t see this as being any different. It’s just going to be that those horses that are very bad bleeders genetically will phase themselves out of the gene pool because they are not going to be competitive.”For now, it is a guessing game as to which current stallions and mares might produce bleeders.In 2014, a group of Australian researchers at the University of Sydney published a 10-year study to determine if horses could be genetically predisposed to epistaxis. The study reviewed 1,852,912 individual performance records of 117,088 racehorses in Australia, where Lasix is banned for racing. As part of that study, the researchers investigated the pedigrees of 715 sires and 2,351 dams.“Our research showed that epistaxis is moderately heritable,” co-author Dr. Claire Wade, professor and chair of Computational Biology and Animal Genetics, said in an email. “This implies that it is a complex trait that can be selected against in a breeding population. Exercise-induced pulmonary hemorrhage (EIPH) is the underlying condition that, when severe, manifests as epistaxis. That epistaxis is inherited implies that EIPH is also inherited. The inheritance is not a simple Mendelian trait [dominant, recessive], and so it is unlikely to be controlled by DNA-based testing. Because horses with epistaxis are less successful on the racetrack in the long run, there should be selection against the disorder. I expect that this is more likely to be achieved by indirect selection against breeding stock through their exclusion from racing than by bloodstock agents avoiding purchase of animals with epistaxis in their pedigree.”Wade’s co-author and emeritus professor of Animal Genetics, Dr. Herman Raadsma, agreed, adding, “Although heritable, a significant component is non-genetic or chance occurrences for reasons we may not necessarily know why or predict in advance.”Kevin McKathan, who since 1988 has operated McKathan Brothers Training Center and bloodstock agency with his now late-brother J.B., said what he looks for in a horse probably isn’t going to change.“When I buy or sell horses, I would say maybe it’s a 10%-15% possibility that you end up with a true bleeder,” he said. “Until we have the data that shows the mare was a bleeder, the stallion was a bleeder, the mare’s mother’s mother was a bleeder, I’m not sure how we could make that decision on their genetics,” McKathan said.“If you’re buying a horse that’s already racing on Lasix, that would definitely be a concern. But I think we’re going to have to figure out a way, if they ban Lasix, to get along with those horses that have breathing problems. Hopefully, you won’t get one.“I don’t believe we breed bleeders necessarily,” McKathan continued. “I believe certain horses are traumatized, where they do bleed; but I believe with a different training method, there’s a possibility that these horses won’t bleed. So we’re going to have to learn how to train around that problem if they take Lasix away from us.”Dr. Robert Copelan, 94, was the track veterinarian for Thistledown near Cleveland in the 1950s, before Lasix was approved for race day. Part of his job was to observe every horse during unsaddling after a race and enter the names on the Vet’s List of horses that visibly bled.“The riders sometimes would come back with blood all over their white pants and their silks, just a horrible sight to see, right in front of the grandstand where they took the saddles off those horses,” he recalled.Copelan estimated 1%-3% of those pre-Lasix runners would end up on the Vet’s List, which required trainers to lay them off for a certain number of days and then demonstrate they could breeze a half-mile for Copelan without bleeding. Every additional incident of bleeding within a 365-day period for that same horse increased the mandated time off. For the third or fourth incident within a year, depending on the jurisdiction, the horse would be ruled off for life. These bleeder regulations still exist in every jurisdiction.Copelan is concerned about these horses and the horsemen who invest in them.“Let’s say you and I have teamed up in a partnership and we’re going to buy a couple of horses, and we’ve had good luck together,” he said. “Now we’re interested in a horse, and we’re going to have to give between $850,000 and a million for him. We buy him, and now when he turns two and we have him ready for his first race, the son of a gun turns out to be a bleeder. Are we going to sit there and say, ‘Oh, what bad luck!’?”Prospective buyers can examine sale horses for imperfections, such as throat abnormalities and those that potentially could cause lameness, but there is no way to tell if a horse will be a bleeder. When examined, any damage found in the airway and lungs from a prior respiratory illness sets off warning bells, but with no guarantee the horse will develop EIPH when it races. Every fall of the hammer becomes a roll of the dice for these buyers.Terry Finley, president of West Point Thoroughbreds, said the scenario Copelan described is an unfortunate situation, but he doesn’t know how often one could reasonably expect it to happen.The owner’s responsibility will be to decide what to do about horses with EIPH. Management changes, added preparation, veterinary care before and after a race, and time off to allow the horse’s lungs to heal all add up to larger training and veterinary bills. Many owners will have to take a hard look at the long-term plan for horses with EIPH that can’t be competitive without special handling. Is the added expense worth it, or should they retire the horse? It’s unlikely to be desired as breeding stock, even with a stellar pedigree. What happens to it then?“The more I talk to people all around the country, they see this situation, while not perfect, as a compromise,” Finley said of the move to ban Lasix. “They see it as a way to move past this issue, at least in the short term, and they understand that it’s not going to be perfect. I’ve thought about this a lot, and I’ve talked to a lot of people. If you look at it at the fringes, it could present some problems. But, by and large, the hope is that this is going to be better for the greater good, and that’s what we hope will be the situation at some point in the future.”](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/517636f8e4b0cb4f8c8697ba/1596789747311-JB0OSD4DJHZAXIIZVZ7R/Z200125_eclipsesportswire__04580+%281%29.jpg)