Walter Rodriguez

Article by Ken Snyder

We see them every day in the news—men, women and children trudging north across Mexico, searching for a brighter future in the best bet on the globe: the United States. For most Americans, we don’t foresee them winning that bet like our ancestors did generations ago. The odds against them are huge.

But long shots do come in.

Walter Rodriguez was 17 years old when he pushed off into the Rio Grande River in the dark from the Mexican bank, his arms wrapped around an inner tube to cross into the U.S. The year was 2015, which differs from 2023 only in scale in terms of illegal immigration. He crossed with two things: the clothes on his back and a desire to make money he could send home. How he ended up making money and yes, quite a bit of it at this point, meant overcoming the longest odds imaginable and, perhaps, a lot of divine intervention.

Getting here began with a long six-week journey to the border from Usulutan, El Salvador, conducted surreptitiously and not without risk and a sense of danger.

His family paid $5,000 to a “coyote” (the term we’ve all come to know for those who lead people to the border).

“They would use cars with six or eight people packed in, and we would drive 10 hours. We’d stay in a house. Next morning, they would drive again in different cars, like a van; and there would be more people in it.”

Three hours into a trek through South Texas brush after his river crossing, the border patrol intercepted him. He first went to jail for several days. After that, he was flown to a detention center for illegally migrating teenagers in Florida with one thread tying him to the U.S. and preventing deportation: an uncle in Baltimore. After a month there and verification that his uncle would take him in, Walter flew to Baltimore and his uncle’s home in Elk Ridge, Maryland. From El Salvador, the trip covered about 3,200 miles.

He worked in his uncle’s business, pushing, lifting and installing appliances, doing the work of much larger men despite his diminutive size. More than a few people marveled at his strength. Ironically, and what he believes divinely, more than a few people unknowingly prophesied what was to come next for Rodriguez. Particularly striking and memorable for Walter was an old man at a gas station who looked at him and said twice. “You should be a jockey.”

For Walter, the counsel was more than just a chance encounter with a stranger. It is a memory he will carry his whole life: “This means something. I think God was calling me.”

Laurel Park just happened to be 15 minutes from where Rodriguez lived in Elk Ridge.

Whether by chance or divine intervention, the first person Rodriguez encountered at Laurel was jockey J.D. Acosta. Walter asked in Spanish, his only language at the time, “Where can I go to learn how to ride? I would like to ride horses.”

He couldn’t have gotten better direction. “I’ve got the perfect guy for you,” said Acosta. That was Jose Corrales, who is known for tutoring and mentoring young jockeys—three of whom have won Eclipse Awards as Apprentice of the Year and a fourth with the same title in England. That was Irish jockey David Egan who spent a winter with Corrales in 2016 before returning to England. He piloted Mishriff to a win in the 2021 Saudi Cup.

“This kid—he came over out of the blue to my stable,” recalled Corrales. “He said, ‘I’m so sorry. Somebody told me to come and see you and see if maybe I could become a jockey.’”

Corrales sized up Rodriguez as others had, echoing what others had told him: “You look like you could be a jockey.”

The journey from looking like a jockey to a license, however, was a long one; he knew nothing about horses or horse racing.

Perhaps surprisingly for someone from Central America, where horses are a routine part of the rural landscape, Rodriguez was scared of Thoroughbreds.

He began, like most people new to the racetrack, hot walking horses after workouts. Corrales also took on the completion of immigration paperwork that had begun with Rodriguez’s uncle.

His first steps toward becoming a rider began with learning how to properly hold reins. After that came time on an Equicizer to familiarize him with the feel of riding. The next step was jogging horses—the real thing.

“He started looking good,” said Corrales.

“I see a lot of things. I told him, ‘You’re going to do something.’”

Maybe the first major step toward becoming a jockey began with the orneriest horse in Corrales’ barn, King Pacay.

“I was scared to put him on,” said Corrales. In fact, the former jockey dreaded exercising the horse, having been “dropped” more than a few times by the horse.

Walter volunteered for the task. “Let me ride him,” Corrales remembered him saying before he asked him, “Are you sure?”

Maybe before the young would-be jockey could change his mind, Corrales quickly gave him a leg up.

“In the beginning, he almost dropped him,” said Corrales, “but he stayed on and he didn’t want to get off. He said, ‘No, I want to ride him.’”

“It was like a challenge I had to go through,” said Rodriguez, representing a life-changer for him—a career as a jockey or a return to his uncle’s business and heavy appliances.

The horse not only helped him overcome fear but gave him the confidence to do more than just survive a mean horse.

“I started to learn more of the control of the horses from there.”

Using the word “control” is ironic. In Rodriguez’s third start as a licensed jockey, he won his first race on a horse he didn’t control.

“To be honest, I didn’t know what I was doing. I just let the horse [a Maryland-bred filly, Rationalmillennial] do his thing. I tried to keep her straight, but I didn’t know enough—no tactics, none of that. We broke from the gate, and I just let the horse go.”

Walter Rodriguez receives the traditional dousing from fellow jockey Jorge Ruiz after winning his first career race at Laurel Park, 2022.

It was the first of 11 victories in 2022 in six-and-a-half months on Maryland tracks and then Turfway Park in Kentucky. Earnings were $860,888 in 2022; and to date, at the time of writing not quite halfway through the year, his mounts have earned a whopping $2,558,075. Most amazing, he led Turfway in wins during that track's January through March meet with 48. He rode at a 19% win rate.

Next was a giant step for Rodriguez: the April Spring meet at Keeneland, which annually draws the nation’s best riders.

He won four races from 39 starts. More significant than the wins, perhaps, is the trainer in the winner’s circle with Rodriguez on three of those wins: Wesley Ward.

How Ward came to give Rodriguez an opportunity goes back to 1984, the year of Ward’s Eclipse Award for Outstanding Apprentice. One day on the track at Belmont, he met Jose Corrales. On discovering Corrales was a jockey coming off an injury and battling weight, Ward encouraged him to take his tack to Longacres in Seattle. The move was profitable, leading to a career of over $4.4 million in earnings for Corrales and riding stints in Macau and Hong Kong.

The brief exchange on the racetrack during workouts began a friendship between Corrales and Ward that continued and is one more of those things that lead to where Rodriguez is today as a jockey.

Corrales touted Rodriguez to Ward, who might be the perfect trainer to promote an apprentice rider. Ward’s success as a “bug boy” eliminates the hesitation many of his owners might have against riding apprentices.

He might be the young Salvadoran’s biggest fan.

“I can’t say enough good things about that boy. He’s a wonderful, wonderful human being and is going to be a great rider.”

He added something that is any trainer’s sky-high praise for a jockey: “He’s got that ‘x-factor.’ Horses just run for him.”

Corrales, too, recognizes in Rodriguez a work ethic in short supply on the race track. “A lot of kids, they want to come to the racetrack, and in six months they want to be a jockey. They don’t learn horsemanship,” said Corrales. “You tell Walter to do a stall, he does a stall. You tell him to saddle a horse, he saddles the horse. He learns to do what needs to be done with the horses.

“He’s got the weight. He’s got the size. He’s got a great attitude. He works hard.”

Ward was astonished at something the young man did when one of his exercise riders didn’t show up at Turfway one morning: “He was leading rider at the time but got on 15 horses that morning and that’s just one time.“ Ward estimated Rodriguez did the same thing another 25 times.

“He’ll do anything you ask; he’s just the greatest kid.”

Ward recounted Rodriguez twice went to an airport in Cincinnati to pick up barn workers flying back to the U.S. from Mexico to satisfy visa requirements. “He’d pick them up at the airport from the red-eye flight at 4:30 in the morning and then drive them down to work at Keeneland.”

Walter on Wesley Ward’s Eye Witness at Keeneland.

With Rodriguez’s success, talent is indisputable, but Corrales also credits a strong desire to reach his goal combined with an outstanding attitude. Spirituality, too, is a key attribute developing in extraordinary circumstances in his home country.

When Rodriguez was three years old, his father abandoned him and his mother. As for her, all he will say is, “She couldn’t raise me.” His grandmother, Catalina Rodriguez, was the sole parent to Rodriguez from age three.

He calls his grandmother “three or four times a week,” and she knows about his career, thanks to cousins that show her replays of his races.

Watching him leave El Salvador was difficult for her, but she saw it as necessary to the alternative. He credits her for giving him “an opportunity in life. Otherwise, I would be somebody else, doing bad things back at home.”

Surprisingly, her concerns for her grandson in the U.S. were more with handling appliances than 1,110-pound Thoroughbreds.

“When I was working with my uncle, she wasn’t really happy; she wasn’t sure about what I was doing.

“But I kept saying to her, let’s have faith. Hopefully, this is going to be okay. Now she realizes what I was saying.”

His faith extends to the latest in his career: riding at Churchill Downs this summer. “One day I got on my knees and I said to God, ‘Please give me the talent to ride where the big guys are.’“

Gratitude is another quality that seems to come naturally for Rodriguez. After the Turfway Park meet at the beginning of April, he flew back to Maryland to provide a cookout for everybody in Jose Corrales’s barn.

He also sends money to El Salvador, not only to his grandmother but to help elderly persons he knows back home. During the interview, he showed pictures of food being served to people in his village at his former church. At least a significant portion of that is financed by Rodriguez’s generosity.

“I love to help people. It will come back to you in so many ways. I’ve seen how it came back to me.”

According to Corrales, there have been discussions about a possible movie on Rodriguez, who just received his green card in June of this year.

“These days with immigration, crossing the border and all the trouble we’re having—to have somebody cross the border and have success, it’s a blessing,” Corrales said.

A blessing, for sure, but one that was meant to be. Walter encapsulated his journey and what happened after he went to Laurel Park with a passage from a psalm in the Bible: “The steps of a good man are ordered of the Lord.”

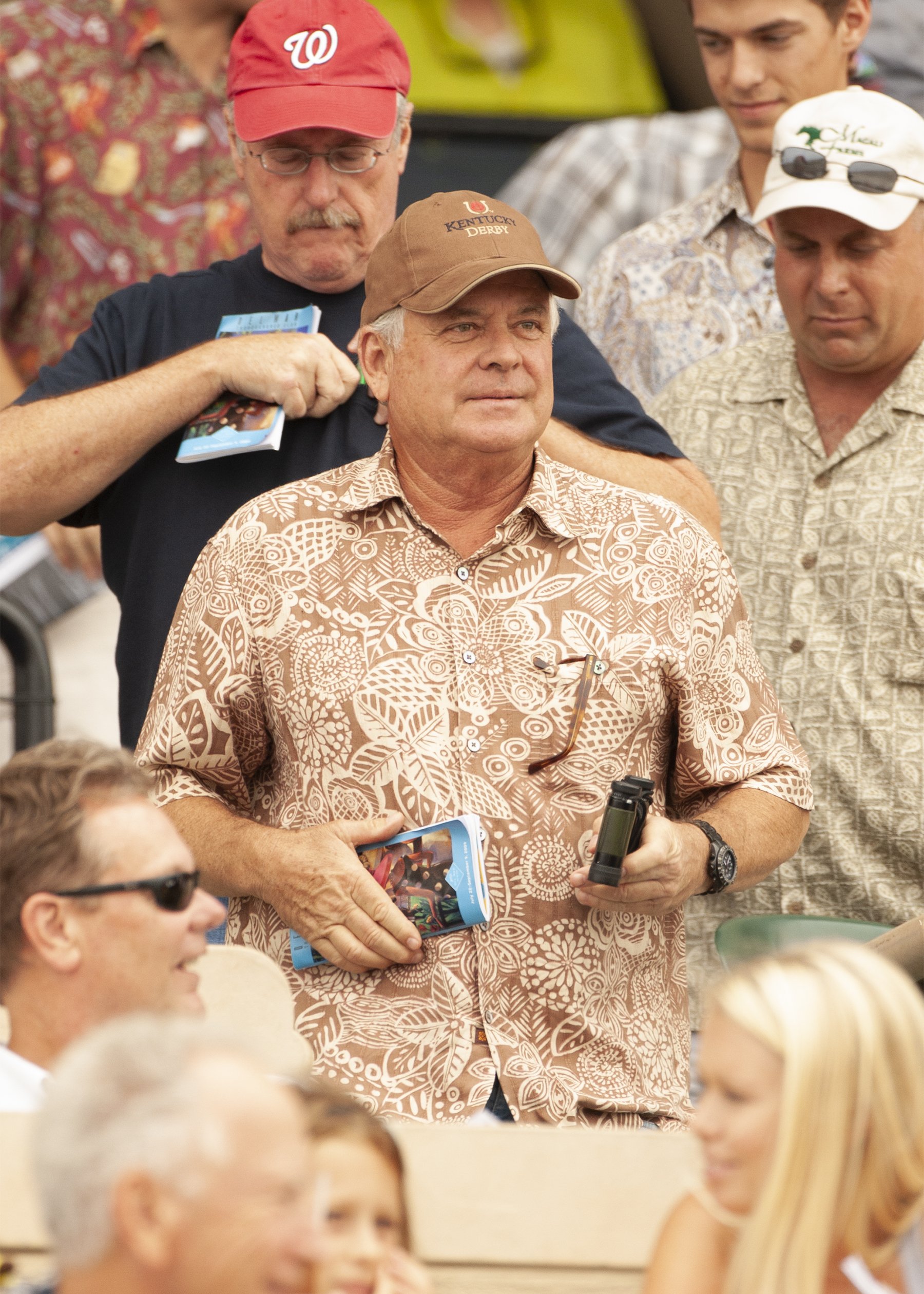

Earle Mack - The Eclipse Award winning humanitarian philanthropist

By Bill Heller

Many people wonder what they can do to help people in need. Other people just do it. That’s how Earle Mack, who received an Eclipse Award of Merit earlier this year for his contributions to Thoroughbred racing, has fashioned his life. So, at the age of 83, he flew from his home in Palm Beach, Florida, to the Hungary/Ukraine border to deliver food and clothing to desperate Ukrainian refugees who fled their homes to escape the carnage of Vladmir Putin’s Russian thugs.

“I’m going to the front,” he declared in early March. “I woke up and said, `I have to do my part.’”

He’s always done more than his part. Besides being an extremely successful businessman, he was the United States Ambassador to Finland. An Army veteran, he is helping veterans with PTSD through a unique equine program. He supports the arts. He is an active political advocate. And he has enjoyed international success with his Thoroughbreds—breeding and/or racing 25 stakes winners, including 1993 Canadian Triple Crown Winner and Canadian Horse of the Year Peteski, a horse he purchased from Barry Schwartz; $3.6 million winner Manighar, the first horse to win the Australian Cup, Ranvet Stakes and BMW Cup; and 2002 Brazilian Triple Crown winner Roxinho. Two of his major winners in the U.S. were November Snow and Mr. Light. And he founded the Man o’ War Project, which helps veterans with PTSD via equine-assisted therapy.

“I love my country,” he said. “I love the arts. And horse racing is in my blood.”

Literally, Ukraine is in his blood. He discovered through Ancestry.com that he is two-thirds Ukrainian. “My great grandfather fled Ukraine to go to Poland,” he said.

So he had to go to Ukraine.

“He’s an extraordinary man,” owner-breeder Barry Schwartz, the former CEO of the New York Racing Association and the co-founder and CEO of Calvin Klein, Inc., said. “I’ve known [Earle] a very, very long time. He loves the horse business. He’s extremely philanthropic. I’ve been on the board with him for the Cardozo Law School at Yeshiva University [where Earle served as chairman for 14 years]. I get to see a different side of him. He’s smart. He’s articulate. He’s a class act.”

In early March, Mack, a trustee of the Appeal Conscience Foundation, called owner/breeder Peter Brant (a fellow member of that foundation) and former New York State Governor George Pataki (whose parents are Hungarian) to head to one of the most dangerous locations on the planet. Brant supplied the plane. His wife, Stephanie (Seymour), brought 40 big duffle bags of clothing, “She spent over $30,000 buying the clothes,” Mack said. “I took clothes off my racks. I brought all the fruit that we could find and a couple boxes of chocolate.”

The delegation landed on March 10th, two weeks after Russia’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine, and began an unforgettable experience. Displaying yet another talent, he wrote about his trip in an op-ed published by The Hill, an American newspaper and top political website, on March 16th:

“How would you feel, in this day and age, if you were fleeing your home with only the few things you could carry in freezing winds and winter temperatures? How would you feel sitting in your car for 17 hours, waiting to cross a border, all the while worried that the sound in the sky above might be a missile or bomb bringing certain death? How would you feel trapped in your basement or a public bomb shelter, food and water running out, afraid to leave and face death? How would you feel if your city was under attack and you watched as civilians were shot up close by Russian soldiers and neighborhoods were rubbled from faraway artillery? How would you feel leaving your fathers, husbands and brothers behind to fight against impossible odds?

“This is what I have wondered, listening to heartbreaking stories that have brought me to tears, told by Ukrainian refugees on my recent trip to the Hungarian border and into the Ukrainian city of Mukachevo, where hundreds of thousands have fled the war with Vladmir Putin’s Russia.”

Mack went on to share his experience of Ukraine, “Ukraine has cold winds. Thirty-five feels like 15. Lots of hills and farmland. Peter and his 17-year-old daughter stayed at the border. We went into Mukachevo, a city of about 20,000 to 25,000 people. At that point—two weeks into the war—there were more than 500,000 people in that area, hoping that there’s something to go back to.

“We went into a children’s hospital ward filled with children. We looked at a COVID ward with kids lying down. We went into a school converted into a dormitory. We saw all these kids, ages two to eight with their mothers. Men, 16 to 65, weren’t allowed to cross the border. The kids were crying. Not much to eat. We brought in the fruit. We brought in the chocolate.

“I started handing out the chocolates. These kids ate all the chocolate. I have the empty box. I put it on one of the six-year-old kid’s head and started singing, `No more chocolates; no more chocolates.’ That kid takes the empty box and puts it on another kid’s head. They’re all singing, ‘No more chocolates; no more chocolates.’ When I was leaving, the director of the center came running after me and said this is the first time they laughed in two weeks.”

Mack wrote of this bittersweet moment in his story in The Hill: “As we prepared to leave, there was a 12-year-old girl who literally begged me to take her with us. I can’t describe how hard it was to walk away from this young girl whose life is forever changed.”

This from a man whose life is forever changing.

Terry Finley, the CEO of West Point Thoroughbreds, said, “Although we’ve never owned a horse together, we try to make a point to spend a couple of races at Saratoga, just the two of us in the box. I pick his brain. He’s such a good person. He’s got a world of knowledge. He’s a fun guy. He’s a caring guy—as cool a guy as there is in the industry.”

Peter Brant, Earle Mack, Lily Brant, Christopher Brant & Karen Dresbach (executive vice president of the appeal of Conscience Foundation) before boarding a plane loaded with medical supplies, food, clothing and other essentials for Ukrainian refugees arriving in Hungary

One of four boys born in New York City, Earle’s father, H. Bert Mack, founded The Mack Company, a real estate development company. Earle was a senior partner of The Mack Company and a founding board member of the merged Mack-Cali Realty Corporation. He has served as the chairman and CEO of the New York State Council on the Arts for three years and produced a number of plays and movies. His political action included an unsuccessful attempt to draft Paul Ryan as the 2016 GOP presidential candidate.

His entry into horse racing was rather circuitous. He learned to ride at the Sleepy Hollow Country Club in North Tarrytown, N.Y. “All the juniors and seniors were allowed to use the trails at Sleepy Hollow County Club,” he said. “I was 16, 17. I got to ride on the course. That’s how I learned to ride.”

Just after graduating college, he returned to Sleepy Hollow. “One day, I was dismounting; the riding master who taught me how to ride came over to me and said, `I’m very sorry to tell you this, but my wife has cancer and needs surgery. I need $2,500 to pay for surgery.’ He owned a horse who won a race up in Canada.”

Mack went inside with him to examine the horse’s papers. “I said, ‘I’m buying a $5,000 horse for $2,500’; I bought it on the spot. I thought this sounds like a good deal. The horse’s name was Secret Star. He stayed in Canada and raced at Bluebonnets and Greenwood. The horse won about $20,000.”

Flush with excitement, Mack bought four horses from George Kellow. “They did well. I said, ‘This game is easy.’”

He laughs now—well aware how difficult racing can be. That point was driven home in the late 1960s after Mack had graduated from Drexel University with a Bachelor’s Degree in Science and Fordham School of Law. He served in the U.S. Army Infantry as a second lieutenant in active duty in 1959 and as a first lieutenant of the Infantry and Military Police on reserve duty from 1960–1968.

In the late 1960s, he was struggling with his Thoroughbreds. “My horses weren’t doing that well,” he said. “I bought two seasons to Northern Dancer. His stud fee was $10,000 Canadian. When the stud fee came due, I didn’t have the money to pay for it. I walked over to my dad’s office. I said, ‘I need a loan.’ He said, `No, you’re in the wrong business. Get out of that business.’”

Mack walked back to his office. “I started to think, ‘How am I going to get this money?’ Twenty minutes later, my father threw a check on my desk. Then he got down on his knees, and he said, ‘Son, sell your horses. Get out of this business. You’re not going to make money in this business.’”

He might have had a good thought. “The two Northern Dancers never amounted to anything,” Mack said.

That seemed like the perfect time to follow his father’s advice and give up on racing. But Mack stayed. “I just loved the business; I loved being there. I loved the horse. I loved the people. I just loved it—that’s why. I still love the sport. I love to go to the track. I love to support the sport. I love to help any way I can. I’ve given my time and my efforts to our industry.”

That list is long: Board of Trustees member of the New York Racing Association 1990-2004; chairman of the New York State Racing Commission (1983–89); member of the New York State Thoroughbred Racing Commission (1983–1989); member of the Board of Directors of the New York State Thoroughbred Breeding and Development Corp (1983–89); and senior advisor on racing and breeding to Governor Mario Cuomo and Pataki.

The Earle Mack Thoroughbred Champion Award has been presented annually since 2011 to an individual for outstanding efforts and influence on Thoroughbred racehorse welfare, safety and retirement.

He has been a long-time backer of The Thoroughbred Retirement Foundation and the Grayson Jockey Club Research Foundation.

In 2011, he established the Earle Mack Thoroughbred Retirement Foundation Award. The first three winners were Frank Stronach, Dinny Phipps and famed chef Bobby Flay.

His brother Bill, the past chairman of the Guggenheim Museum and Guggenheim Foundation, also owned horses, including $900,000 earner Grand Slam and $500,000 earner Strong Mandate. But he did better with investments in art. “He bought art; I bought horses,” Earle said. “Guess who did better? Much better.”

But who’s had more fun? Mack bought Peteski, a son of 1978 Triple Crown Champion Affirmed out of the Nureyev mare Vive for $150,000 from Barry Schwartz after the horse made his lone start as a two-year-old, finishing fifth in an Ontario-bred maiden race on November 14, 1992.

Earle Mack, Barry Irwin, jockey Jamie Soencer and Team Valor connections celebrate Spanish Mission winning the $1 million Jockey Club Derby Invitational Stakes at Belmont Park in 2019

After buying Peteski, Mack sent the horse to American and Canadian Hall of Famer Roger Attfield. Peteski and Attfield put together an unbelievable run: seven victories, two seconds and one third in 10 starts, finishing with career earnings of more than $1.2 million.

Mack told the Thoroughbred Times in October 1993, “Bloodstock agent Patrick Lawley-Wakelin originally called the horse to my attention. I’d always liked Affirmed as a stallion and together with my connections, we thoroughly checked the horse out before I bought him. I was lucky to get him. There were other people trying, too, but I had long standing Canadian relations and was able to move fast. They knew I was a serious player.”

All Peteski did was win the Canadian Triple Crown, taking the Queen’s Plate by six lengths; the Prince of Wales by four lengths and the Breeders by six. He followed that with a 4 ½ length victory in the Gr. 2 Molson Million. In his final start, Peteski finished third by a head as the 7-10 favorite in the Gr. 1 Super Derby at Louisiana Downs.

“The thrills he’s given me are something money can’t buy,” Mack told Thoroughbred Times. “One of the reasons for staying in Canada for the Triple Crown was because of the wonderful and nostalgic feelings of my youthful days spent racing there. This is the greatest horse I’ve ever owned.”

Earle with jockey Gerald Mosse at Newbury Racecourse in 2019

Mack would race many other good horses, but the ones who may have had the greatest impact are the anonymous ones he helped locate who participated in the Man o’ War Project—perhaps Mack’s greatest gift. In 2015, out of his concern about the mental health crisis facing veterans, he created and sponsored the Man o’ War Project at Columbia University’s Irving Medical Center to explore the use of and scientifically evaluate equine-assisted therapy to help veterans suffering from PTSD or other mental health problems. Long-term goals are to test that treatment with other populations. Immediate results have been very promising.

There is a sad reality about veterans: more die from suicide than enemy fire. The project was the first university-led research study to examine the effectiveness of equine-assisted therapy in treating veterans with PTSD.

“My love for the horse and my great respect and empathy for our soldiers bravely fighting every day for our country and not getting the proper treatment led me to do this,” Mack said. “Soldiers come home with the strain of their service on the battlefield. The suicides are facts. There was no science or methodology proving that equine-assisted therapy (EAT) could actually and effectively treat veterans with PTSD. All reports were anecdotal.”

The project was led by co-directors Dr. Prudence Fisher, an associate professor of clinical psychiatric social work at Columbia University and an expert in PTSD in youth; and Dr. Yuval Veria, a veteran of the Israeli Armed Forces who is a professor of medical psychology at Columbia and director of trauma and PTSD at New York State Psychiatric Institute.

After a pilot study of eight veterans lasting eight weeks in 2016, 40 veterans participated in a 2017 study also lasting eight weeks. Each participant underwent interviews before, during and after the treatment period and received follow-up evaluations for three months post-treatment to determine if any structural changes were occurring in the brain. Each weekly session lasted 90 minutes with five horses, using the same two horses per each treatment group. The veterans started by observing the horses and slowly building on their interactions from hand-walking the horses, grooming them and doing group exercises.

“We take a team approach to the treatment,” Fisher said. “We have trained mental health professionals, social workers, equine specialists and a horse wrangler for an extra set of eyes to ensure safety during each session.”

Marine Sergeant Mathew Ryba at the Bergen Equestrian Center

The results have been highly encouraging. A 2021 article in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry concluded “EAT-PTSD shows promise as a potential new intervention for veterans with PTSD. It appears safe, feasible and clinically viable. These preliminary results encourage examination of EAT-PTSD in larger, randomized controlled trials.”

Mack was ecstatic: “This is a scientific breakthrough. You could see the changes. It’s drug free. Before, you had to take more and more and more drugs. Before you know it, you’re hitting your family.”

The Man o’ War project works. It helps. It could possibly help a lot of people besides veterans. That would be the biggest victory of Mack’s remarkable life.

“That would be my Triple Crown,” he said.

Mack was asked how he does what he does in so many varied arenas. “Pure tenacity, drive and 24/7 devotion to the things that were important to me and public service,” he replied. “I’ve devoted my life to public service, my business, horses and the arts.”

And now, to Ukraine. Lord bless him for that.

The Hirsch family legacy

by Annie Lambert

California’s Bo Hirsch has always relished horse racing, but winning last year’s Breeders’ Cup Filly & Mare Sprint (Gr. 1) with his homebred, Ce Ce, was “icing on the cake.”

“My goodness, what a thrill,” Hirsch remarked about Ce Ce’s championship. “You talk to people that don’t know anything about horse racing, mention winning a Breeders’ Cup, and they ask what it is. I tell them the best comparison I could give was the Olympics. If you win a Breeders’ Cup race, you’ve pretty much won a gold medal. We won a gold medal last year, and I’m tickled pink.”

Ce Ce, a six-year-old by the late Elusive Quality, accelerated near the top of the Del Mar stretch, overcoming a trio of leaders, including defending champion Gamine, to garner the $1 million purse. Ridden by Victor Espinosa, it was trainer Michael McCarthy’s second Breeders’ Cup victory.

Hirsch’s love of the sport harkens back to his father, businessman Clement L. Hirsch, who left giant footprints across the racing industry before his death in 2000 at 85. The elder Hirsch was instrumental in co-founding the Oak Tree Racing Association at Santa Anita as well as the current Del Mar Turf Club organization. Ce Ce’s Breeders’ Cup success at Del Mar was homage to Clement.

Clement also invested in pedigree lines that continue to produce the likes of Ce Ce. And, Bo’s love of his father and appreciation for the sport to which he introduced him could not be clearer.

“I just love this business; there’s nothing like it, you know?” Bo, 73, asked rhetorically. “It’s a grownup toy store—a wonderful toy store.”

Founding Father

Clement Hirsch’s common sense, drive and dry sense of humor no doubt contributed to his success in business and racing. He attended Menlo College near San Francisco during the 1930s.

While still in college, Clement and some friends bought a washed-up Greyhound dog for very little money. The owner was going to euthanize the canine because it was too broken down to race. The boys brought the dog back to good health, ended up racing it and were excited the process culminated with winning some money. That may have been the future horse owner’s first taste of racing, but it was most certainly his catalyst into the business world.

It didn’t take long to figure out the “people person” with street smarts would choose business over school. Having learned about caring for dogs with the Greyhound, Clement—who served a stint in the Marines during World War II—realized people, mostly, fed their pets table scraps in that era. He began selling a meat-based dog food, door-to-door, out of the trunk of his car. The entrepreneur wound up building that effort into Kal Kan Pet Foods, which he ultimately sold to the Mars Corporation that now markets it under their Pedigree label.

By 1947, Clement decided to invest some of his success into Thoroughbred racing. He hired Robert H. “Red” McDaniel, an established trainer in Northern California. They claimed Blue Reading, a $6,500 outlay, which went on to win 11 stakes, including the 1951 Bing Crosby Handicap, San Diego Handicap and Del Mar Handicap, earning $185,000. From that introduction, Clement was hooked; he owned horses for the rest of his life.

Breeders Cup winner CeCe is a third generation homebred, and Hirsch plans on extending the pedigree line

More Horses, Same Trainer

Clement hired Warren Stute to train his horses in 1950—his second and final trainer. Stute remained his trainer until Clement’s death, 50 years later—a feat we may likely never see again.

“My father could be difficult, and Warren had a mind of his own,” Bo pointed out. “I remember someone asking my father, ‘How did you guys stay together so many years? How could you put up with Warren all those years?’ He said, ‘I just turned down my hearing aide.’”

“It worked,” Bo added with a laugh.

The line of bloodstock that Ce Ce hails from began when Clement attended a sale at Hollywood Park in March 1989. Upon walking in, Mel Stute, Warren’s brother, was bidding on a horse. Mel told his brother’s owner the horse was going over his price range, but that it was worth the money. Clement did make one bid, which dropped the hammer at $50,000.

Hirsch could hardly believe he bought a horse with one wave of his arm, but the result was fortuitous. He had purchased the two-year-old, Magical Mile (J.O. Tobin – Gils Magic, by Magesterial).

The colt won his first out, a maiden special weight, at Hollywood Park just two months later. He broke the track record that day, running the 5-furlongs in :56 2-5, while winning by 7 ½ lengths. He came back in July to win the Hollywood Juvenile Championship Stakes (G2), ultimately earning $131,000 (7-4-0-1) during his career.

“I remember my father being interviewed once when the horse was really doing well,” Bo recalled. “Someone said, ‘You must be getting Derby fever.’ My father said, ‘No, no, no, that’s not realistic; I wouldn’t think in that area, it’s such a long ways off.’ There was a hesitation, then he said to the guy, ‘But, for what it’s worth, we’re trying to get the name Magical Mile changed to Magical Mile and a Quarter.’”

The Howell S. Wynne family owned Magical Mile’s dam, Gils Magic, a mare with no money earned in only one start. Clement tried more than once to buy the mare, but to no avail. He did, however, show up at the sales every time one of her offspring was offered.

“The next great one was Magical Maiden,” Bo said. “He kept trying to buy Gils Magic, but they wouldn’t sell, so he bought what he could from that line. It built up.”

Magical Maiden (by Lord Avie) was a multiple graded stakes winner of $903,245. She is the second dam on Ce Ce’s pedigree. Magical Maiden foaled Ce Ce’s dam, Miss Houdini by Belong To Me in February 2000.

Miss Houdini, trained by Warren Stute, only made a total of four starts at two and three, but managed to win the Del Mar Debutante Stakes (Gr. 1) just about six weeks after a successful maiden special weight debut. Her two wins and a second totaled lifetime earnings of $187,600.

Clement and Warren imported Figonero from Argentina in 1969. The four-year-old stallion was already a winner in his homeland, but he made waves in the United States. Figonero ran third to Ack Ack in both the American Handicap and the San Pasqual Stakes. He won the Hollywood Gold Cup with the late Alvaro Pineda riding. Rumor has it, Stute tore out a wooden deck in his backyard and replaced it with a swimming pool shortly after the Gold Cup.

Pineda was also aboard when Figonero set a world record for 1 1/8 miles while winning the 1969 Del Mar Handicap at Del Mar.

“Figonero was a good one,” Bo remembered. “He ran multiple races in just a few weeks. He won an overnight race, ran third in the American Handicap and came back, ran against [1969 and 1970 co-champion handicap male] Nodouble in the Gold Cup and won the darn thing. They took him back to Chicago in the mud and he didn’t do well, came back here and broke the world record in the Del Mar Handicap.”

“That record lasted about three years until this horse called Secretariat broke it,” he said, chuckling.

Big Ideas

During the late 1940s, Clement got the idea to establish a racetrack in Las Vegas, Nevada.

After acquiring the land and finding investors, Hirsch ran into a multitude of setbacks, which slowed down his project. Eventually the frustrations ended and they had a racetrack. Hirsch brought in some of his own horses to encourage his friends and others to bring more livestock, according to Bo.

“They tried to get it going and it just didn’t work,” the younger Hirsch commented. “[Some local businessmen] offered to buy him out, and he was smart enough to sell. They were only in business for a very short time. I think it was a tough deal there with the heat in the summer and just getting the people to go to the races. They were gamblers, but not racetrackers—a different kind of gambler.”

Hirsch gave Las Vegas a shot and it didn’t work out, but it’s possible his vision was just a little ahead of its time.

By 1968, Clement was securely ensconced in the Thoroughbred industry as a breeder and owner. The businessman had a “never let an idea lay idle'' mindset; so when he noticed unused calendar dates between the summer meet at Del Mar and Santa Anita’s winter meet, the wheels began turning.

Hirsch organized a meeting with Robert Strub, owner of Santa Anita at the time, Lou Rowan, an owner/breeder; and equine insurance broker, veterinarian Jack Robbins and a few others to discuss options for utilizing Santa Anita on those dark dates. The organizers were able to get their dates approved, and the Oak Tree Racing Association at Santa Anita had their opening meet the following fall.

“Once they got approval for the dates, they came back to finalize things with Strub,” Bo said. “Jack Robbins told me the story that they’re in a room and Robert Strub looks up and says, ‘You know, if this thing doesn’t work out, it’s going to cost us, Santa Anita, a few million bucks.’ That was a lot of money in those days. My father said, ‘You’re covered.’ Strub looked at my father and said, ‘You’ve got a deal.’ Then they shook hands, which was the way they did it in those days.”

Pivotal in creating Oak Tree was Clement Hirsch’s concept that the organization be created as a non-profit.

Clement Hirsch (dark jacket), seated alongside his friend and Oak Tree racing association co-founder Dr Jack Robbins and surrounded by other oak tree board members

“None of the board members or executives, which were all horsemen, got salaries,” Bo explained. “For the betterment of the horse racing business, they took all that money and put it back into the business and charitable organizations.”

Shortly after the Oak Tree negotiations, Del Mar (owned by the state of California) came up for an operational bid. Clement put together another group of horsemen figuring the non-profit structure would also work for Del Mar.

“My father put the [Del Mar Thoroughbred Club] group together and they bid for the track and the racing dates,” recalled Bo. “Nobody could compete with a non-profit organization. It was a great idea and, of course, they got it. The same group runs it today; it’s been a very successful organization. I’d like to see more of this happen in horse racing across the country.”

Blended Family

The Hirsch family was an interesting blend of families as Bo was growing up. Clement was married four times, so Bo has full-siblings, half-siblings and step-siblings, which he jokingly calls “a motley group.” He was the only one of those eight kids to take an interest in the racehorses.

“The horse business either gets in your blood or it doesn’t,” Bo opined. “It got into mine; I just loved it the minute I saw it. My father never encouraged me; he thought I was stupid to get in it.”

“He told me I was going to lose my money,” he added with a laugh. “But he loved it, and he couldn’t defend himself for being in the horse business in a practical way. He was successful at it, and I know now why he was in it. I’m in it and I understand: It brings you such joy.”

During the mid-1950s, Clement built his CLH Farm in Chatsworth, outside of Los Angeles. He stood several stallions there over the years, with limited success. When he relocated his family to Newport Beach, he moved the farm to Poway in San Diego County.

Bo said he enjoyed the farm as a kid and did his share of shoveling manure and riding ponies, but he always preferred “to hang out on the front side” at the track.

Similar Guys

Like his father, Bo, who resides in Pacific Palisades, is a businessman. After graduating from the University of Southern California, he worked as a stockbroker until the market dropped in 1972; then he began looking for a different career path.

His father had sold the pet food company but retained a pioneering company, Rocking K Foods, which provided portion-controlled meals for hospitals and the like. There was also a cannery there where the company canned foods for the government to send to the troops in Vietnam.

Out of the blue, Bill Gray, president of the company who ran the operation for the retired Clement, asked Bo if he’d consider leaving the brokerage firm to work for him in sales and marketing. Bo replied, ”When do you want me to start?”

Bo Hirsch

After a short scrimmage with his father over his qualifications regarding a job in the food industry, Bo settled into the job. He ultimately developed the Stagg Chili food lines, which he later sold to Hormel.

“My father always wanted to make sure you knew what you were doing,” Bo explained. “He wanted to make sure you heard both sides of a story, to be sure you were doing what you wanted to do and the right thing to do. He’d always challenge you, take the other side to challenge you and make sure you believed in what you were doing.

“He did it at home with his kids, too. It was a wonderful lesson to learn to get all the facts before you start making decisions—get in there and figure it out. That was just the kind of guy he was and why he was so successful in all the things he ever did.”

Clement’s energy and unique personality lent itself to memorable stories remembered by those who knew him.

“Alan Balch [now executive director of California Thoroughbred Trainers Association] told me the story of Fred Ryan [an executive at Santa Anita at the time] being in a heated phone conversation,” Bo recalled with a chuckle. “Ryan slammed the phone down and, looking at Alan, said, ‘That damn Clement Hirsch—he’d kick a hornet’s nest open just to get a reaction!’”

When Clement passed away, his son stepped up to continue developing the pedigrees his father had been procuring. Miss Houdini, now 22, was foaled just prior to Clement’s death, but greatly enriched her family tree.

“I started with Warren Stute,” said Bo, regarding his racing stable. “When [Warren] passed, I went to his nephew, Gary Stute—Mel Stute’s son. I still have horses with him. Gary’s a good horseman and we’ve done well; plus, he’s a lot of fun. He’s my cigar smoking partner.”

“I’ve had as many as four trainers at one time, just trying to feel things out. I liked them all, but I don’t think it’s the best way to go in the long run, at least not for me.”

Cece ridden by victor espinoza, wins the breeders’ cup filly and mare sprint at del mar 2021

Bo sent horses to Michael McCarthy on a recommendation from Michael Wellman, a long-time California owner/breeder.

“If there is a trainer that is a harder worker than Michael McCarthy, they’re living on a day that is longer than 24 hours,” Bo said. “He just works night and day; it’s his life.”

Anticipating Greatness

Miss Houdini has obviously been a wonderful producer for Hirsch. Her current honor roll offspring, Ce Ce, has won eight of her 16 starts, earning $1,753,100 through last year’s aforementioned Breeders’ Cup win. The mare has captured additional group races including the Beholder Mile (Gr. 1), Apple Blossom Handicap (Gr. 1), Princess Rooney (Gr. 2) and the Chillingsworth Stakes (Gr. 3).

Miss Houdini foaled a colt in 2006, Papa Clem—a Kentucky-bred by Smart Strike trained by Gary Stute, which also made his dam proud. Papa Clem broke his maiden at two on his third try. At three, he went on to win the Arkansas Derby (Gr, 2) and finished his career as a four-year-old by winning the San Fernando Stakes (Gr. 2). Between those Gr. 2 races, however, Papa Clem contested two legs of the Triple Crown.

“[Papa Clem] ran fourth in the Derby; he just got beat a head for second,” Bo recalled. “He was sandwiched between Pioneerof The Nile and Musket Man, and there was some bumping. We ran him in the Preakness and probably shouldn’t have. He just looked dead to me in the barn. He was usually jumping around, and he wasn’t. I think he ran sixth. We gave him some time off prior to the San Fernando and then retired him to stud.”

Bo has seven mares in his arsenal. Stradella Road (Elusive Quality) is a full sister to Ce Ce. She was a winner at three and four, ran third in the Lady Shamrock Stakes and has lifetime earnings of $130,169.

The stakes-placed Magical Victory (Victory Gallop), earner of $66,928, also resides in Bo’s broodmare band. She produced Hot Springs (Uncle Mo), a winner of five races and $272,343 including the Commonwealth Turf Stakes (Gr. 3).

Unraced Mama Maxine, named after Bo’s mother, is the dam of Ready Intaglio (Indygo Shiner) that won seven races, earning $197,418 while winning seven races, including the Canadian Derby (Gr. 3). She also foaled the stakes-placed Mama Said No (Exaggerator). Mama Maxine will be bred to California sire Grazen (Benchmark) this year.

“I always want to keep involved in California,” Bo said. “They have a good program to get you to breed here. I’m going to bring Mama Maxine out here; she’s a nice mare from the family. The other six will stay in Kentucky. I have a two-year-old now, four yearlings; and in the next couple of months, we’ll have a few more. They do add up.”

All the people involved with his racing operations are appreciated by Hirsch. Those in Kentucky include Kathy Berkey at Berkey Bloodstock. His mares reside at Columbiana Farm in Paris, while Rimroc Farm in Lexington starts his babies. Some go into advanced lessons with Bryan “Scooter” Hughes as they progress. When he has a layup or mares in California, they go to Rancho Temescal, north of Los Angeles.

Hirsch and connections celebrate CeCe’s Breeders’ Cup triumph

The Hirsch passion for the Thoroughbred racing and breeding industry is multigenerational. His wife Candy enjoys going to the races and spending time with the horses at the barns. Their daughter Hayley, 29, was excited when Dad named an auction purchase after her: Hayley Levade (Dialed In). The thus unraced three-year-old is training with Stute for her debut.

“Horses are great animals, and this business makes you get up in the morning and keeps you going,” Bo said with a smile. “It’s a wonderful thing to be in the racing business and have this opportunity and the thrills you get. Anticipation is the name of the game. You look and you dream about this and that… I’ve been very lucky.”