Mario Baratti on how he’s created a classic winning stable in the heart of Chantilly

Mario Baratti is sitting behind the desk in the spacious office of his stable off the main avenue leading into Chantilly, munching a croissant in between second and third lots. I decline his offer of breakfast, and we quickly agree to communicate in French and to use the friendly “tu” form instead of the more formal “vous”.

Above the trainer’s right shoulder, a large watercolour depicts a scene of Royal Ascot, “it was a wedding gift and it was too big for the house so it has a perfect place here… The colours are beautiful and it’s a wonderful source of inspiration!” The walls are also adorned with photos and a framed front page of French racing daily Paris-Turf showing Baratti’s two Classic winners to date, Angers who lifted the German 2000 Guineas at Cologne in 2023 and Metropolitan who propelled his handler onto the big stage with a first Group 1 victory in the Poule d’Essai des Poulains a year later. There is plenty of space left for memorabilia which seems sure to come to celebrate wins in the future.

Born and raised in Brescia in North-West Italy near Lake Garda, Mario Baratti has a slightly different profile from several of his compatriots who are now successfully operating in Britain and France. The 35-year-old does not hail from a big racing family and he has little experience of training in his native country.

He explains, “My father was a great sportsman and was good at a lot of sports. Between age 18 and 25 he rode over jumps as an amateur. I started riding very early, at age four or five, and showjumped and evented when I was young and then started riding as an amateur as soon as I could. I was a true amateur as I didn’t start working in racing until I was 19. I was lucky to ride about 70 winners, in Italy but also in Britain and France, in a relatively short career in the saddle.”

A couple of summer stints with John Hills in Lambourn as a teenager further fuelled the young Mario’s passion for racing and he soon joined Italy’s legendary trainer, Mil Borromeo in Pisa, “Mil Borromeo was a great trainer, very sensitive and with an amazing capacity to listen to his horses. His objective was to create champions and he succeeded many times during his career. He was on the same level as the top trainers from England, Ireland and France from the time. He was very sensitive and attentive to his horses. My official title with him was assistant but I was so young I was more of an intern.”

After a year with the Classic Italian trainer, Borromeo advised the young Barrati to spread his wings and continue his education, both in racing and academically.

The Botti Academy

The logical port of call was Newmarket and the stable of training’s rising Italian star of the time, Marco Botti. “I used to ride out in the mornings and go to Cambridge in the afternoons to learn English. The original plan was to spend just a year in England to pass a language exam, but after I passed the exam, Marco Botti proposed the position of assistant if I stayed with him. When I started he had less than 50 horses and during the four years I was there the number rose to over a hundred so it was a real growth period. I had the good fortune to ride horses like Excelebration who was exceptional, and to travel to Dubai, or Santa Anita for the Breeders’ Cup... He had six or seven real high-quality Group horses, who could travel and win abroad.

I learnt many things during my time with Marco and the most important was probably how to manage the horses in the best possible way to optimize their potential. I think the secret to his international success is that he travels his horses at the right moment. He understands when a horse is tough enough to go abroad, and he doesn’t take them too early in their careers.”

After four years in the buzzing racing town of Newmarket, it was time to continue the learning curve and despite an offer to join another compatriot, Luca Cumani, Baratti remembers, “everyone advised me to go to America or Ireland.” So the young Italian found himself in rural County Kilkenny. “Jim Bolger said he would only take me if I stayed for three years, but in the end I cut my time short. It was a very good experience and I learnt a lot about breaking in yearlings and working with youngsters. I learnt what I could in a short time as I was only there for three or four months, an intense experience of work and life. Mr Bolger is a real horseman, who is tough on his horses but always manages to produce champions. He can do things that others cannot allow themselves to do, because he breeds and owns a lot of the horses himself.”

Despite the prestige of his Classic-winning mentor, Baratti was unable to settle in Ireland. “I like the countryside, but I was isolated. I was 25 years old and never saw or spoke to anyone and the lifestyle wasn’t for me. So one day I told him, “I can’t stay three years”, and he said, “you want to train in London? You can’t train in London!” I’ll never forget that! But he understood and in the end he said, “I’ve taught a lot of top professionals, McCoy, O’Brien, but it’s up to you if you want to leave. I hope that you find someone as good as me…””

Pascal Bary an inspiring mentor

Next stop was France, and Baratti took advantage of a couple of months before his start date with his next boss, Pascal Bary, to join fellow Italian Simone Brogi who had recently set out training in Pau. He also spent a month with Brogi’s former boss, Jean-Claude Rouget, at Deauville’s all-important August meeting.

“The time helped me to learn French and integrate into the French ambiance, which wasn’t easy. I found it much tougher to settle in France than in Newmarket. As a foreigner I felt less well received. Even at Newmarket, I started as an assistant when I was 18 years old, with no experience, and it was tricky to manage a team of 25 or 30 staff. But when I started here it was even more difficult to handle the French staff. They would say to me ‘I’ve never done that in 30 years and I’m not going to start now…’ During the early days with Pascal Bary, I thought that France wasn’t going to be for me. Then it became a personal challenge and I decided to stick it out. Now, Pascal Bary is one of the closest friends I have here in Chantilly, but at the start he wasn’t an easy boss. It took two years, of the four that I was there, before we built up a real relationship. On my side, I was very respectful, and I saw him as someone who was very reserved, so we kept our distance. I was in awe of him and his career. He wasn’t interested in just winning races, he wanted to develop the best out of his horses. That’s why he had such a great career. 41 Group 1 wins in a 40-year career is a huge achievement. He won Dianes, Jockey-Clubs, Poules, Guineas, Breeders Cups, the Irish Derby… He’s the only French trainer to win the Dubai World Cup. He started off going to California for the Breeders’ Cup when he was very young. He would dare to step into the unknown, because at the time it was much more complicated to travel around the world.

I was lucky to be there at the time of Senga - who won the Prix de Diane and Study of Man won the Prix du Jockey-Club. So I worked with top horses, who were perfectly managed, and many of them were for owner-breeders. Very early in the season, when the grass gallops opened, he would immediately pick out the three or four standout horses and plan their programme. He could tell right away which ones had talent ‘this one will debut in the Prix des Marettes at Deauville… ‘ I remember that year the filly did exactly that and won; it was Senga and she went on to win the Diane.

When you spend time with someone at the end of their career, there is more to learn. Pascal Bary had a superb training method, and he had the success he did because he was very firm in his decisions. He’s not someone who changes his mind every day, and there aren’t many people like that nowadays. He was very sensitive to his horses and always sought to create champions. I try to keep in mind his method.”

Changing dimension

The string for third lot is now ready to pull out and we make our way through the yard which has been adapted to accommodate an expanding string.

“We recently acquired the next-door yard and we knocked through the walls of a stable to make a passageway between the two. I now have 73 boxes in these two yards, plus 15 at another site which has the benefit of turnout paddocks.”

Through a gate in the hedge at the back of the courtyard and we are straight onto the famed Aigles gallops as the sun starts to break through the clouds on what had begun as an overcast morning.

“It’s a magnificent site; we are so lucky to have such beautiful surroundings and for me to be able to access the gallops on foot.” As we make our way to the walking ring in the trees where the Baratti string circles before and after work each morning, the trainer tells me, “I still ride out every Sunday, bar only two or three weeks in the year. I think it’s important to exercise as many as we can on a Sunday and if I ride two, that’s a help to the staff and a real pleasure for me too.”

The string of around twenty juveniles, many still unraced, passes before the trainer who gives multilingual orders. “Here we speak Italian, French, English, Arabic and Czech,” he explains, “we try to all speak French but of course sometimes we communicate in Italian, especially when things get heated! We’ve more than doubled in size since last autumn and so we built up the new team throughout the winter and in spring. It’s all coming together now. For the first few years everything went very smoothly, but there were only half a dozen members on the team! When you get up to 25, it’s a different story.”

The team includes a couple of former Italian trainers who left their country and now work as managers for the burgeoning Baratti stable, plus veteran Filippo Grasso Caprioli, Mario’s uncle who was a leading amateur rider in Italy in his time. “He “just” rides out, he doesn’t have a position of responsibility but he does give us the benefit of his age and experience!”

Another vital member of the team is Monika, Mario’s Czech-born wife. “We first met at the Breeders’ Cup when I travelled with Planteur and she was the work rider of Romantica for André Fabre. When I first moved to France we both lived in the same village, 100m away from each other but we never bumped into each other. We met again four years after I moved to France. We’ve been together now for seven years and married this spring. Monika is an excellent rider and she also takes care of the accounts, but her most difficult job is taking care of our two small boys. I think she sometimes comes into the yard for a break!”

As we trudge across the damp turf to the Réservoirs training track, Baratti expands on his choice of Chantilly. “When I was in Newmarket I thought I would never leave, but then it was logical to continue here after I had done my time with Pascal Bary. And of course, the French system is very beneficial compared to elsewhere in Europe. The facilities here in Chantilly are second to none. When I first started I used to use all of the gallops but now I have my routine and regularly use Les Réservoirs. I often use the woodchip but there is plenty of choice. Once you have understood how each track works then it’s simple.”

The first group of two-year-olds canter past, and Mario runs through some of the sires represented: Siyouni, Lope de Vega, Wootton Bassett, for owners such as Nurlan Bizakov, Al Shir’aa, Al Shaqab and powerful French operators such as Laurent Dassault, Bernard Weill and others.

“This is the first year that I’ve had such a good panel of owners, and a better quality of horses. It is certainly thanks to Metropolitan and the successful season we had last year. In previous years, we did well with limited material, and we managed to win Listed or Group 3 races which isn’t easy when you only have 20 horses. This year we have more horses but haven’t won any big races yet (he laughs nervously) but they will come…”

Indeed days after the interview, the stable enjoyed a prestigious Group success on Prix du Jockey-Club day with the Gérard Augustin-Normand homebred Monteille, a sprinting filly who was trained last year by the now-retired Pascal Bary.

“It's very important to have owners who also have a breeding operation. They have a different outlook on racing and they are often the ones that produce the really top horses. They expect good results, of course, but they understand the disappointments and are generally more patient. The other owners are important too, and Metropolitan, who we bought at the sales, is the proof of that.”

Classic memories

Understandably, a smile widens across Mario’s face as he remembers the day when the son of Zarak lifted the Poule d’Essai des Poulains to offer the trainer his first major Classic winner.

“I was only in my fourth year of training, it wasn’t even in my dreams to win a Poule so soon in my career. It’s hard to describe, the joy was enormous. The fact that we ran in the race again this year, with a very good horse (Misunderstood) but everything went wrong, makes you realise now how difficult it is for everything to go right on a day like that. I always thought that Metropolitan was an exceptional horse. We were far from favourites in the Poule but I knew we had a good chance of winning. The owners rang me on the morning of the race and asked, ‘Mario do you think we can win?’ and I said Yes! He had finished fifth in the Prix de Fontainebleau and we had ridden him to avoid a hard race, but still, many observers overlooked him. Apart from in his last race on Champions Day, he never put a foot wrong. He confirmed his class when third in the St James’s Palace Stakes in a top-class field and then was beaten by the best four-year-old miler in Europe, Charyn, in the Jacques le Marois. And at the time, we only had three or four three-year-olds in the yard, so the percentage was amazing.”

Baratti had already tasted Classic glory a year earlier, thanks to Angers (Seabhac) who won the Group 2 Mehl-Mülhens-Rennen (German 2000 Guineas). A first successful international raid from the handler who learnt from some of the industry’s specialists.

“You travel if your horse is very, very good, or not quite good enough,” he explains.“If you travel to Royal Ascot, you have to be exceptional, the same for the Breeders’ Cup. But for Germany you can take a decent horse who isn’t quite good enough for the equivalent races here. Angers had finished second in the Prix Machado which is a trial for the Poule d’Essai. I already had Germany in mind for him if he was placed in the Machado, and he went on to win well in Cologne. Every victory is very important, the key is to aim for the right race within the horses’ capabilities. Each horse has his own “classic” to win, with a made-to-measure programme.”

Many expatriate Italian trainers target Group entries in their native country, but Baratti is not keen to explore this option. “I have never had a runner in Italy. I did make an entry recently but we ended up going elsewhere. Italian black-type is very weak for breeding purposes, so it’s not really worthwhile for me to race there. There are a lot of good professionals in Italy but I don’t really have much connection with them because I’ve never worked over there, I left when I was young.”

A realistic approach

Baratti’s adopted homeland of France has recently announced austerity measures for the forthcoming seasons to compensate for falling PMU turnover and pending the results of a recovery plan which aims to increase the attractivity of French racing for owners and public. France Galop prize money will be reduced by 6.9%, equating to 10.5 million euros during the second half of 2025 and 20.3 million euros for following seasons until a hoped-for return to balance in 2029.

“It’s normal,” says the Italian pragmatically. “It’s better that they make a small reduction now than wait two or three years and have to make drastic cuts. It’s necessary to take the bull by the horns, not like how it was in Italy when they let the situation decline and then it became too hard and too late to redress. We are fortunate to be in a country where prize money is very good compared with our neighbour countries in Europe, so a small reduction won’t affect people too much.

Owning racehorses is a privilege and a passion. It is a luxury and people should treat it as such, not buy horses as a means to earn money. If you buy a magnificent yacht, it costs a fortune, and it’s pure outlay. Money spent on having fun. Nowadays, a lot of people invest in racehorses for business purposes, but they need to have the necessary means. If you are lucky to buy a horse like Metropolitan and then sell him for a lot of money, that’s another story, but it wasn’t the aim at the outset.”

He remembers an important lesson on owner expectations from former mentor Pascal Bary. “I was surprised once when Mr Bary received some foreign owners in his office. They wanted to buy ten horses. He told them, the trainer earns money, not every day, but he tries, in any case his objective is to earn money, the staff earn money and the jockey earns money. Normally, the owner loses money. If things go well, they don’t lose much, if they go very well they can break even, and when it’s a dream, then you can make money, but that’s the exception to the rule. The guys had quite a lot of money to invest and they were there, open-mouthed. In the end they chose another trainer. But Mr Bary was right. If I decide to buy a horse tomorrow for 5,000€, I have to consider that 5,000€ as lost. If I want to invest, I should buy a house.

His explanation was very clear and that’s how racing should be understood. It would be nice to have a group of friends buy a horse, but it costs a lot. Ideally it should just be for pleasure, like membership at the golf, or tennis. It's an expenditure. And if in the end you end up winning, then all the better. And it can happen. Bloodstock agents do that for a living but it’s their profession. My owners are in racing for the pleasure.”

With an upwardly-mobile, internationally-minded and ambitious young trainer, Baratti’s owners certainly look set for a pleasurable ride over the forthcoming seasons, and the office walls are unlikely to remain white for long.

Cavalor Trainer of the Quarter - Joseph Murphy - who saddled Cercene to win the Gp.1 Coronation Stakes at Royal Ascot

“I have been training for fifty years. Fifty years waiting for a Group One winner, we have been second and third in Group Ones, so we’ve been knocking on the door, but didn’t open it – today, we opened it. This is fifty years of work by the family, going from a small yard, switching from National Hunt to Flat, and buying horses and believing that they are going to be good. It is a lifetime's ambition to have a Group One winner.”

So said Joe Murphy at Royal Ascot after saddling Cercene to become the longest-priced winner of the Coronation Stakes, which deservedly earns him our Trainer of the Quarter.

Murphy trained his first winner in 1977 and has enjoyed a steady stream of success in Group 2 and Group 3 races, despite the wait for a Group 1. Gustavus Weston, Only Mine, Euphrasia and Ardbrae Lady were probably his best-known horses before Cercene delivered something of a surprise, though her form certainly didn’t reflect her long odds.

Now that the dust has settled, Murphy has a chance to reflect on Cercene’s achievement, although it was business as usual at his Crampscastle yard in Fethard, County Tipperary, when Vorfreude won the Ulster Derby at Down Royal the following afternoon, breaking his maiden at the sixth time of asking, having run up against some very good horses but nevertheless never finishing out of the first three this season.

“Cercene is just a really beautiful filly to have,” says Murphy. “The secret to her is to have the courage not to work her. When she’s fit we just leave her to herself, she seems to know. She may be small but she has a strong physique and a very strong, healthy constitution. She loves her work and she loves being in training. After Ascot we planned to give her a break for a week, but you could see straight away she wanted to be out on the gallops and in her usual routine. She was ridden out on Tuesday, back in her happy place.”

It is hard to know why Cercene was sent off at 33-1, having finished so well in the Irish 1000 Guineas and with many of the Coronation Stakes runners behind her at the Curragh. Now the plans, not the odds, are big.

“We are playing with the Irish Oaks in our minds, but really we’d be more aiming for the Nassau Stakes and Matron Stakes and the Breeders’ Cup, the gaps fit in quite well.”

Murphy acknowledges the help of his wife Carmel, son Joseph and daughter-in-law Olive, and the whole team at Crampscastle, “all good staff” and reveals Fethard is the perfect training centre. “The farm has always been a training establishment, originally Larry Keating was here and it has all the facilities, the original grass gallop and a nine-furlong (1800m) and seven-furlong (1400m) sand and fibre gallops, plus a three-furlong (600m) warm-up.”

Reflecting on his early beginnings in Kilkenny with his first two horses, Haybob and Vibrax, Murphy was privileged to be a part of what he describes as a “wonderful academy” under Willie O’Grady at Killeen. “There were so many great names there, Eddie O’Grady, Timmy Hyde, Mouse Morris, it was an unbelievable academy. A wonderful place to be and to get insight into the training of racehorses.”

That insight has certainly stood well to Murphy and with the likes of Lord Massusus, Vorfreude and Shiota, all, like Cercene, on an upward career path, it shouldn’t be another long wait until his next Group One.

How to choose the most effective supplements to support your horse

Good horse people want to do the right thing for the horses in their care. They want to help them perform to the best of their ability, and they want to help them to do that consistently, throughout the racing or competition season. Nutrition is a vital part of that. Every season, stables are presented with a long list of supplements, and every rep says theirs is the best. How do you know if you need to spend money on supplements, at all? If you conclude that you do, how do you sort the wheat from the chaff and pick the best one?

There are, essentially, only three reasons to feed a supplement:

To improve the balance of the daily ration,

To fill the gap between good daily nutrition and the increased requirements of horses under stress, and

To address specific health concerns.

Daily Ration Balance

First, remember that horses’ guts have adapted to digest roughage, and they need it. Hay (or grass, if you are lucky enough to have it) is the basis of a good daily ration.

You only need to feed a concentrated feed (the stuff you buy in a bag, like a Racehorse or Stud Farm Mix) to meet the additional protein, energy, vitamin, and mineral requirements that horses in work, growing, or breeding have. If the concentrate feed you choose has been prepared by a major feed company, it will generally be balanced for those things already, and they will essentially meet the daily needs of horses, when fed with forage. If you are having to correct deficiencies of energy or protein in your daily feed, consider picking a better-balanced concentrate feed for your particular horses.

In some parts of the world, grass isn’t plentiful, so forage is generally fed in the form of hay or green feed. Depending on the type of hay you choose, calcium and phosphorus balance might have to be adjusted with a daily supplement. You should ask your nutritionist or veterinarian to help you to get that right. In general, though, grains are high in phosphorus and low in calcium. Lucerne (Alfalfa) is high in calcium, while grass hays are generally lower in it. Feeding a mixture of grass hay and Lucerne as the main part of your daily ration, will likely mean that calcium and phosphorus will be close to right in your total ration, including the right concentrated feed. As an added bonus, Lucerne is a very good source of cost-effective and bioavailable protein for horses.

If you don’t need to add other stuff to your daily ration, don’t. With a few exceptions, it’s money wasted. Adding individual nutrients can produce no results or disrupt the balance of a good feed and actually have negative results.

Exceptions to the Rule

If the daily ration has selenium provided in an inorganic form, such as sodium selenite or selenate, have your veterinarian check blood selenium. Some horses will absorb and use those forms of selenium well, and others might not. Selenium has a very narrow therapeutic range (the amount they need is only a little bit less than the amount that is toxic), so it’s dangerous to over-supplement. If some horses need more, pick a supplement that provides selenium in an organic form like selenomethionine or selenocysteine. Yeast-based selenium is mostly a mixture of the two.

In a hot climate, some additional table salt or a salt block will be needed. Every horse, even spelling ponies, need access to a salt block.

Stabled horses and those in the Middle East don’t always get much grass. If horses aren’t getting fresh, growing grass, vitamin C might be low. Although it is often included in prepared feeds, it can be unstable, especially in hot climates, and levels can quickly drop. You might consider supplementing with vitamin C when horses are under extra stress. Vitamin C and the B group vitamins are water soluble, and they are not stored in the body. As a result, it makes more sense to provide those in supplements, given only when horses are under extra stress and requirements are increased.

When horses are under the added stress of hard work, transport, racing, competition, high heat and humidity, or ill health, requirements for many nutrients are increased. Feeding a daily ration designed for horses in hard work will generally provide energy, protein, fat soluble vitamins, and mineral levels to meet their overall needs, but some nutrient requirements will be increased beyond that, just at the time horses are under stress. B vitamins, for instance, will be needed in doses between 20 and 200 times requirements during times of added stress. If they were fed doses at this level on a daily basis, much of the dose would pass out in the urine. That is money wasted. On days they are travelling, racing, or sick, they would need more, absorb it, and use it. That’s money well spent.

At the same time as horses are under extra stress and need more nutrients, they will often go off feed and drink less than usual. Supplements will certainly be helpful, at those times, to fill the gap between good daily nutrition and the amount of nutrients they are eating and drinking voluntarily.

When you need a supplement for times of increased stress, it’s really important to read labels carefully. Ask yourself, these questions:

Does it have the right stuff? Is it complete?

Is the balance right?

Are the forms of nutrients and the doses going to meet the requirements of your horses?

To help answer these questions, consider the following:

Completeness

Metabolism is complex, requiring a broad range of essential nutrients. You can’t just feed two or three of them and hope to support performance, recovery, health, and metabolism. A lot of one nutrient doesn’t make up for deficiencies in another. If you ran out of food in your house and tried to just live on a big bag of salt, you wouldn’t last long. It is, therefore, important to consider if the supplement you are evaluating is complete enough to meet the complex requirements of equine physiology.

Balance

The balance between nutrients is equally important. Some nutrients are required for the uptake and function of other nutrients. (These supportive and cooperative nutrients are called co-factors.) Too much or too little of one nutrient may result in deficiencies or toxicities of other nutrients. Imbalances, therefore, can have a negative impact on health, performance, and recovery. At a minimum, imbalances in a feed or supplement can cost you money and have no effect at all.

For example, vitamin C is required for the absorption of iron from the gut. Without it, iron passes straight through the gut and out in the manure. Vitamin E binds with iron and reduces its absorption, causing much of it to be wasted. So, for horses to use dietary iron effectively, it has to be given with Vitamin C and without Vitamin E.

Bioavailability

Bioavailability refers to how well nutrients are absorbed and used. While this is partly related to the composition and balance of nutrients in a product, this is also about the form each nutrient is provided in. Some forms are more easily absorbed and used by the body than others.

The trace element chromium, for example, exists in several different forms. The form of chromium found in a chrome bumper on a car is, as you can imagine, not very digestible at all. The more organic forms like chromium picolinate (for people) or those incorporated into yeasts (a form often found in daily feed supplements for horses) is very easily absorbed and then used by cells. Minerals including calcium, magnesium, iron, cobalt, copper, zinc, selenium, and manganese can all be provided in a variety of forms, each of which have differences in their bioavailability.

In general, inorganic forms of nutrients are less well used than organic forms, though that is not always a reliable rule. Zinc oxide is one of the more bioavailable forms of zinc, whereas zinc chelate forms a big molecule that can be too big to be well absorbed. In most cases, though, minerals provided as gluconates, lactates, and amino acid or protein complexes are well used.

When reading labels, you should note whether the amount of the ingredient or the amount of the active nutrient is listed. For instance, Iron Bioplex, in which iron is bound to amino acids, contains only about 10% iron. If a label says a product contains 400mg of iron per dose, that means that a dose contains about 4000mg of Iron Bioplex yielding 400mg of very well absorbed and used iron. If the label says a product contains 400mg of Iron Bioplex per dose, then it really only has 40mg of actual iron. Make sure that you check those details carefully when reading labels and comparing products.

Doses and Nutrient Requirements

Do the doses of nutrients meet science-backed nutrient requirements? Caution! This might require math before you can measure a supplement against published nutrient requirements.

Labels will include the quantity of each nutrient, but those might be listed per kilogram or per dose. They might be in milligrams (mg), grams (g), or kilograms (kg), pounds (lb), ounces (oz), parts per million (ppm), percentages, or in some cases, a combination of units. All of these must be converted to the same units as the published nutrient requirements, and all have to be calculated per dose. It sounds seriously confusing, and it can be, but it’s also vitally important. If math isn’t your thing, ask a nutritionist for help. You can look up “NRC requirements” yourself or ask your nutritionist or veterinarian for help with this, too. Many feed companies have in-house nutritionists, and this can be a good way to get help, for a minimal charge or even for free, if you don’t have your own nutritionist.

Here's a tip to help make things easier:

If labels are easy to understand, and you can tell, at a glance, what you are feeding your horse in a single dose, then the manufacturer probably believes their formulation will stand up to scrutiny. If you have to perform too many calculations to figure out what you are giving, there’s a fair chance that the formulation isn’t great.

In any case, take the time to do the math and make sure you are comparing apples to apples before picking a supplement to spend your money on.

Addressing Specific Conditions or Concerns

Once the ration is properly balanced and nutritional requirements are being met effectively, you might also wish to feed supplements designed to address specific health issues. Nutraceuticals fed for healthy joints and tendons, or as digestive aids are common examples, and nutritional elements (vitamins, minerals, and amino acids) are also marketed for specific concerns. For example, vitamin K1 may support the development of strong cannon bones; biotin is fed to horses on high grain diets to support healthy hooves; chromium is fed to support muscle cells; and a variety of nutrients are fed to relax highly strung horses or to support red blood cell production in anaemic horses.

If you are looking at extra supplements like these, there are a few important questions to ask.

What scientific evidence is there that these products are likely to be effective?

Are the doses provided the same as the doses that produced good results in studies?

If nutritional elements are to be fed, do the amounts meet NRC requirements and are the cofactors needed for their absorption and effect also provided?

What quality, safety, and security assurance does the manufacturer provide?

Quality, Safety, and Security

How do you know if the product you are looking at contains what is says it does; only a fraction of what it says it has; or way more than it is supposed to have? Even more alarmingly, how do you know it doesn’t contain contaminants that aren’t supposed to be there?

There was an interesting study presented at an American Associate of Equine Practitioners (AAEP) meeting several years ago, in which several nutraceuticals were tested and their actual contents were compared with label claims. Those products were found to contain anywhere between 10 and 200% of the active ingredients that they were supposed to have. That is potentially a huge problem! If a product has too little of an ingredient, it may not be effective and will be a waste of money, but if it has a lot more than it is supposed to have, it may make horses sick or return a positive drug test result. We have already talked about how only a little too much selenium can be toxic, but for some nutrients like cobalt, an essential trace-mineral, feeding too much will produce a positive drug test. Contamination of feed supplements with Naturally Occurring Prohibited Substances, like caffeine, can also produce a positive test.

So, how do you know if a product is manufactured safely and meets its label claims?

This information isn’t generally on the label, but it can be just as important as the label itself. To get it, you either have to know the company management personally and have confidence in their diligence and ethics; you might have to talk to the manufacturer and ask questions; you can look at their website to find a statement about quality management; or you can look for third-party certification of their quality management practices. GMP or ISO certification are good ones to watch for. If a company has either ISO or GMP certification, you can be sure that the supplements they produce will be safe, secure, and generally meet label claims.

If a manufacturer lacks certification, it doesn’t mean they aren’t doing a fabulous job of quality management. They might have a written statement about their commitment to quality management or you might have to ask some questions to be sure. If at least some proportion of finished product undergoes analysis for common contaminants, the concentration of active ingredients, and microbial testing, it will likely be safe. If no testing is done, and the company doesn’t talk about product quality, safety, and security, you should be concerned.

Tip: Be sure to ask every rep that visits your stable about quality management as they will almost certainly be the most readily available source for this information. That is also a simple way to separate the wheat from the chaff. Any rep that can’t talk competently about their company’s quality management program, probably represents a company that doesn’t have one.

Feeding supplements can be necessary for adequately supporting horses, particularly during times of hard training, racing, competition, transport, illness, or stress. It is your responsibility to ensure the supplements you are feeding are necessary, complete, balanced, bioavailable, effective, and safe for health and drug testing. Get good value for money by avoiding under or over-supplementing. Hopefully I have helped you to make good choices, but remember, if in doubt – seek further advice from an equine nutritionist, veterinarian, or feed manufacturer.

Have Horse Will Travel - the international racing opportunities that trainers should be targeting this autumn

Ireland

The Irish Champions Festival takes place at Leopardstown and the Curragh 13th and 14th September respectively. The Curragh boasts the richest day of its year, with a card worth over €2.5m (£2.10m) in total. The highlights are the €600,000 (£503,865) Gp.1 Irish St Leger for three-year-olds and up, the Gp.1 Moyglare Stud Stakes and Gp.1 Vincent O’Brien National Stakes for juveniles and Gp.1 sprint The Flying Five Stakes, each worth €400,000 (£335,900).

The €200,000 (£168,000) Gp.2 Blandford Stakes, the €250,000 (£210,000) Tattersalls Ireland Super Auction Sale Stakes and two Premier Handicaps each worth €150,000 (£126,000) complete the card.

On the opening day at Leopardstown, the nine-race card features five Group races, including the €1.25m (£1.05m) Gp.1 Irish Champion Stakes 2000m (10f), the €400,000 (£335,900) Gp.1 Matron Stakes, €200,000 (£168,000) Gp.2 Solonaway Stakes, €150,000 (£126,000) Juvenile Stakes, €100,000 (£84,000) Gp.3 Tonybet Stakes, the €100,000 (£84,000) Ingabelle Stakes and two Premier Handicaps each carrying €150,000 (£126,000).

In addition to the Irish Champions Festival, the Autumn Racing Weekend will be held at the Curragh 27th and 28th September, which includes the 1400m (7f) €1m (£850,000) Goffs Million, the richest race for two-year-olds in Europe, and the richest handicap in Europe the 3200m (16f) Irish Cesarewitch, worth €500,000 (£425,000). The meeting will also include the Gp.2 Beresford Stakes (€120,000/£101,700) 1600m (8f) for juveniles, celebrating its 150th anniversary, 1200m (6f) Gp.3 Renaissance Stakes (€60,000/£50,800), and 1400m (7f) Gp.3 Weld Park Stakes (€60,000/£50,800).

Irish jumps series

For National Hunt runners, a series of seven 3300m (2m1f) 10-hurdle Irish Stallion Farms EBF Academy Hurdle races will be run in Ireland from October to December. The first is at Cork on 12th October, followed by Fairyhouse 4th October, Punchestown 13th November, Cork 23rd November, Navan 6th December, Naas 15th December and concluding at Leopardstown 29th December.

The races are open to three-year-olds which have not had any previous run under either Rules of Racing or I.N.H.S. Rules other than in Academy Hurdle races. Horses that run in any of the seven races can continue their careers in bumpers, maiden hurdles or Point-to-Points.

Jonathan Mullin, Director of Racing at HRI, explains, “Each of the races offer a Sales Voucher, similar to the IRE incentive for the owners of any eligible Irish-bred horse which wins or is placed either second or third. Each winning owner will receive a €5,000 voucher while the owners of the runner-up and the third-placed horses will each receive €3,000 and €2,000 respectively.”

Additionally, all seven races are part of the Weatherbys National Hunt Fillies Bonus Scheme, so three-year-old Irish-bred fillies that win an Irish EBF Academy Hurdle in 2025 will be awarded an additional €7,500 bonus on top of the race prize money and will still be eligible for the €5,000 scheme bonuses available if subsequently winning a bumper or a steeplechase, but not a maiden hurdle.

Germany

This season, Deutscher Galopp introduced 12 premium handicaps and 15 Premium Racedays, which included seven Group 1 racedays, guaranteeing at least €15,000 (£12,500) in handicaps and maiden races on those days.

The BBAG Auktionsrennen at Mülheim 4th October is worth €52,000 (£43,600), run over 2000m (10f) for three-year-olds offered as yearlings at the 2023 BBAG Sale, while at Krefeld 15th October is the €55,000 (£46,000) Gp.3 Herzog Von Ratibor-Rennen for two-year-olds, over 1700m (8.5f).

The Berlin-Hoppegarten card 3rd October is one of the Premium Racedays and as well as including the 2000m (10f) Gp.3 Preis Der Deutschen Einheit, €55,000 (£46,000) for three-year-olds and up, there is also a 1400m (7f) BBAG Auktionsrennen for three-year-olds offered as yearlings at the 2023 BBAG Sale, and a support card of seven other races from €15,000 (£12,500) to €22,000 (£18,500). Similarly, 19th October at Baden-Baden sees a nine-race card with the guaranteed minimum that also features the Gp.3 €155,000 (£130,000) Preis Der Winterkönigin for two-year-olds over 1600m (8f), and the Gp.3 Herbst Trophy €55,000 (£46,000) over 2400m (12f) for three-year-olds and up.

The 26th October Hannover Premium card includes the €55,000 (£46,000) Gp.3 Herbst-Stutenpreis over 2200m (11f) for three-year-olds and up and two €25,000 (£21,000) juvenile races over 2000m (10f) and, for fillies only, 1400m (7f). The Premium Racedays conclude at Munich 8th November, where the feature is the Gp.1 Grosser Allianz Preis Von Bayern over 2400m (12f) worth €155,000 (£130,000), and another €52,000 (£43,600) BBAG Auktionsrennen, this time for two-year-olds over 1600m (8f) offered as yearlings at the 2034 BBAG Sale.

Sweden

Sweden’s showcase takes place at Bro Park 12th September with a card that includes the Gp.3 Stockholm Cup International (Gp. 3) over 2400m (12f) for three-year-olds and up and worth SEK 1,000,000 (€91,700 / £76,900). The three Listed races on the support card are each worth SEK 550,000 (€50,500 / £42,350) and open to three-year-olds and up, namely the Bro Park Sprint Championship 1200m (6f), the Tattersalls Nickes Minneslöpning 1600m (8f) and the Lanwades Stud Stakes for fillies 1600m (8f).

Later Listed opportunities for three-year-olds up, each worth SEK 400,000 (€36,700 / £30,800), are the 2400m (12f) Skånska Fältrittklubbens Jubileumslöpning and the Peas and Carrots Mile over 1600m (8f) at Jägersro Galopp 5th October, and the 2100m (10.5f) Songline Classic at Bro Park 26th October.

Spain

The highlight of the Spanish season is Champions Day 19th October in Madrid, with a card that includes the Gran Premio Memorial Duque de Toledo over 2400m (12f) for three-year-olds and up, with a value of €50,000 (£42,000) and the Gran Premio Ruban over 1200m (6f) worth €40,000 (£33,500). The €40,000 (£33,500) Gran Criterium for two-year-olds is run over 1600m (8f) 26th October.

British Champions Day

Opening a card that features the British Champions Long Distance Cup (€590,000/£500,000), the British Champions Sprint Stakes ((€590,000/£500,000), the British Champions Fillies and Mares Stakes ((€590,000/£500,000), the Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (€1.36m/£1.15m), the Champion Stakes (€1.53m/£1.3m) and the 1600m (8f) Balmoral Handicap (€295,000/£250,000) is the newly-introduced Two-Year-Olds Conditions Race, worth €295,000 (£250,000), taking the total prize money on the day to €5.13m (£4.35m). Open to two-year-olds, the 1200m (6f) conditions race, like all races at this distance at Ascot, will be run over the straight course.

Turkey

The Jockey Club of Türkiye hosts seven international races in Istanbul at Veliefendi Racetrack, as part of the International Racing Festival run on the first weekend in September. The highlights are the €62,650 (£53,400) 2000m (10f) Gp.2 Anatolia Trophy for three-year-olds up, €190,000 (£162,000) Gp.2 1600m (8f) Topkapi Trophy for three-year-olds up, the €98,700 (£84,150) Gp.3 1200m (6f) Queen Elizabeth II Cup for two-year-olds, €197,500 (£168,400) Gp.3 2400m (12f) Bosphorus Cup for three-year-olds up and the Gp.3 1600m (8f) €142,400 (£121,400) Istanbul Trophy, entries closing 6th August. There is a transport subsidy for international races, $18,000 for round-trip per horse arriving from the continents of America (North and South), Oceania, Africa and Far East countries, €12,000 for round trip per horse arriving from Europe and United Arab Emirates. Any horses scratched from the race after arrival by veterinary report will still receive transportation subsidy. The Gp.3 Malazgirt Trophy for purebred Arabians over 1600m (8f) will also be part of the card.

USA

Kentucky Downs is home to America's only European-style 2000m (10f) all turf racecourse, hosting just seven days racing from 28th August to 10th September, entries closing from 16th August, when emailed expressions of interest must also have arrived for the invitationals. The feature races are the $3.5m (€3m/£2.6m) Gr.3 Nashville Derby Invitational over 2400m (12f) for three-year-olds, the $2.5m (€2.19m/£1.86m) Gr.3 1600m (8f) Mint Millions Invitational and the 2400m (12f) Gr.2 Kentucky Turf Cup Invitational of the same value which is also a "Win and You're In Breeders' Cup Turf" race. Both races are for three-year-olds and up.

Carrying $2m (€1.75m/£1.48m) each are the Gr.3 Kentucky Downs Ladies Turf for fillies and mares three-year-olds and up over 1600m (8f), the Gr.2 Kentucky Downs Ladies Turf Sprint 1200m (6f) for fillies and mares three-year-olds and up, the Gr.1 1200m (6f) Franklin-Simpson Stakes for three-year-olds, the Listed 1600m (8f) Gun Runner for three-year-olds, the Gr.2 1200m (6f) Music City Stakes for three-year-old fillies, the Gr.3 2000m (10f) Kentucky Downs Ladies Marathon Invitational for three-year-olds and up fillies and mares, the Gr.3 2000m (10f) Dueling Grounds Oaks Invitational three-year-old fillies, and the Gr.2 Kentucky Downs Turf Sprint 1200m (6f) for three-year-olds and up which is another of the "Win and You're In Breeders' Cup Turf Sprint Division” races.

Each carrying purses of $1m (€870,000/£738,000) are the Bowling Green Gold Cup Invitational 3200m (16f) for three-year-olds up, the 1600m (8f) Listed Kentucky Downs Juvenile Fillies, the 1200m (6f) Listed Kentucky Downs Juvenile Sprint, the 1600m (8f) Listed Kentucky Downs Juvenile Mile, and the 1200m (6f) Untapable Stakes for two-year-old fillies. The Listed Tapit Stakes over 1600m (8f) for three-year-olds up heads three races worth $500,000 (€437,000/£370,000), alongside the 1600m (8f) NTL Tight Spot Overnight Handicap for three-year-olds up, and the 1600m (8f) Listed One Dreamer for fillies and mares three-year-olds up. Maiden races, already the richest in the world, carry €181,000 (€158,000/£133,300) per race.

“We want to build the Nashville Derby into a race that American and European horsemen alike point to and buy horses for,” says Ron Winchell, co-managing partner of Kentucky Downs with Marc Falcone. “We’ve positioned the Nashville Derby so that it fits into a big-money circuit for three-year-old turf horses.”

The 42nd running of the Breeders’ Cup will be held for a fourth time in Del Mar, California, on the edge of the Pacific Ocean in San Diego “where the turf meets the surf”. Consisting of 14 Grade 1 races with purses and awards totalling more than $31m (€27.11m/£22.97m), the meeting takes place Friday 31 October and Saturday 1st November.

“Our return to Del Mar in back-to-back years marks the continuation of a wonderful collaboration and successful partnership, both with our friends at the track and with the greater San Diego area,” says Drew Fleming, President and CEO of Breeders’ Cup Limited. “We look forward to once again gathering where the turf meets the surf as the world’s best thoroughbreds put on an incredible show.”

“We couldn’t be more excited about hosting back-to-back Breeders’ Cup World Championships and welcoming the very best in international racing back to the town of Del Mar and the greater San Diego area,” said Joe Harper, CEO of the Del Mar Thoroughbred Club. “The Breeders’ Cup represents the pinnacle in world-class racing and the organisation’s willingness to return here again is a testament to the quality of our racing facilities, our idyllic weather, and the warm hospitality shown to our visitors by the local community.”

With 14 championship races held over two days, Future Stars Friday sees the two-year-old championships run for purses upwards of €931,130 (£783,500) and €1.9m (£1.6m). Saturday boasts nine races, culminating with the €6.5m (£5.5m) Gr1 Breeders’ Cup Classic. The “win and you’re in” series consists of 69 of the best races from around the world, from June to October, awarding each winner an automatic and free entry into the Breeders' Cup World Championships.

Bahrain

The Bahrain Turf Series is fairly new to the calendar and has seen just five renewals to date. Running from December through to February, each race carries prize money from €73,750 (£62,850) up to €91,880 (£78,200) with total and the series is designed to attract international runners rated 85-100 to compete against local Bahrain-based horses.

“We believe the time is right to build on the success of the Bahrain Turf Series and expand the international programme to incorporate our season’s premier races,” explains His Highness Shaikh Isa Bin Salman Bin Hamad Al Khalifa, Chairman of the Bahrain Turf Club. “Our most prestigious races, including the Crown Prince’s Cup and the King’s Cup, fall within the Bahrain Turf Series calendar, and are intended to make racing in Bahrain an even more attractive and compelling proposition for international visitors.”

In total, the Series of sprint and middle-distance races comprises of 12 races, six in each division, with each race carrying bonus prizes for the horses accumulating most points in their respective division.

At time of going to press the dates and 2025/26 prize monies were not available, but last year saw significant increases. In December are two 1000m (5f) and two 2000m (10f) races for horses rated 84-100 and a 1200m (6f) and 2000m (10f) race for those rated 80-100.

In January there are two conditions races, over 1000m (5f) and 1800m (9f). February, when the season concludes, sees opportunities for horses rated 80-100 at 1000m (5f), 1200m (6f), 1800m (9f) and 2000m (10f). For those seeking black type, the 2000m (10f) Gr2 Bahrain International Trophy in November for three-year-olds and up is establishing Bahrain as a premier horseracing destination. Run on turf, in 2024 the race was worth €921,858 (£785,315) in total, with €553,115 (£471,178) to the winner.

Entries close 2nd October with supplementary entry stages later in October, but there are three 'Automatic Invitation' races, for the first, second and third from The Royal Bahrain Irish Champions Stakes and the Gp.3 Strensall Stakes at York. The Bahrain Turf Club will provide air tickets for overseas connections and hotel accommodation on a room only basis. Shipment of invited horses will be arranged and paid for by the Bahrain Turf Club.

Australia

The Melbourne Cup Carnival needs no introduction and the Cup itself is only one of 10 Gp.1 racedays during the 22-day season at Flemington. The 3200m (16f) Gr1 Melbourne Cup will be worth A$8.66m (€4.93m / £4.14m) this year, with prize money down to 12th.

During the week there are three €1.8m (£1.6m) weight-for-age Gr1s, the 2000m (10f) Champion Stakes, 1600m (8f) Champions Mile and the 1200m (6f) Champions Sprint. “It is always a great thrill to host international connections who make the journey to Melbourne,” Leigh Jordon, the VRC Executive General Manager, tells us.

More recently the Sydney Everest Carnival held at Royal Randwick and Rosehill Gardens has competed for equal attention, running from 21st September to 9th November, and boasting the world’s richest race on turf, The Everest, over 1200m (6f) in mid-October at Royal Randwick and worth A$20m (€11.3m / £9.5m). The opening day at Royal Randwick features two weight-for-age races, each with a total prize of €615,840 (£520,265) for three-year-olds and up, The 7 Stakes 1600m (8f) and the Gp.2 1100m (5f) Shorts. Randwick later hosts the iconic 1600m (8f) Epsom Handicap, a Gp.1 worth €924,000 (£780,500) and on the Everest supporting card is the €3m (£2.6m) Gp.1 King Charles III Stakes over 1600m (8f).

At Rosehill Gardens, the Hill Stakes over 2000m (10f), and 1800m (9f) Five Diamonds each carry a purse of €1.2m (£1m), with the €6.2m (£5.2m) Golden Eagle over 1500m (7f) the showpiece in November.

Japan

The JRA offers travel incentives for particular overseas horses for Group 1 races and for invited overseas horses for the Japan Cup. The JRA provides air transport costs for the horse and two attendants, the owner, trainer, jockey, and their spouse/partner, and five nights’ accommodation at a JRA designated hotel.

All Japanese Gr.1s are free to enter, or by free invitation, and carry the same declaration fee of €20,200 (£17,500), with significant bonuses from first down to last for the participating winners of designated Gr.1 races globally. The 2400m (12f) Japan Cup is run at Tokyo in November for a purse of €7.3m (£6.3m), Also in November, at Kyoto, the 2200m (11f) Queen Elizabeth II Cup for fillies and mares carries a purse of €1.9m (£1.6m), and The Mile Championship is worth €2.7m (£2.3m). Run on dirt at Chukyo Racecourse, the 1800m (9f) Champions Cup has a total value of €1.7m (£1.5m).

Gerald Leigh Memorial Lectures 2025

The seventh renewal of the Gerald Leigh Memorial Lectures, in association with Beaufort Cottage Educational Trust took place at Tattersalls in Newmarket, England on June 4th.

The Gerald Leigh Charitable Trust was established in 1974, set up in memory of Gerald Leigh, a prominent owner breeder and best known for breeding the highly successful Barathea and Markofdistinction.

His legacy lives on through the trust, which not only reflects his remarkable achievements and lasting influence in the world of Thoroughbred breeding and racing, but also continues his deep passion for scientific advancement and the welfare of horses—both within the racing industry and the wider equine community. The trust stands as a testament to Gerald Leigh’s enduring commitment to excellence, care, and innovation in all aspects of equine life.

Wind ops- the decision making and diagnostics

Tim Barnett MRCVS of Rossdales Veterinary Surgeons, delivered two informative and interesting lectures on wind ops and the decision making and diagnostics relating to them. As we all know, wind surgery addresses upper airway conditions in horses that impair breathing and performance. Key anatomical structures involved include the arytenoid cartilage, vocal folds, epiglottis, and soft palate. Common issues include vocal fold collapse, often causing a whistling noise and linked to progressive recurrent laryngeal neuropathy “roaring”, which severely obstructs airflow. Another frequent problem is dorsal displacement of the soft palate (DDSP), where the soft palate flips over the epiglottis, blocking airflow and causing sudden loss of performance.

Palatal instability often precedes DDSP. Other conditions include medial deviation of the aryepiglottic folds, nasopharyngeal collapse, epiglottic entrapment, and ventral luxation of the arytenoid apex (VLAC). These disorders vary in severity and may be progressive or multifactorial. Barnett clarifies that although surgical interventions target these conditions, outcomes depend on the specific disorder and severity.

Upper airway conditions remain a major cause of poor performance in racehorses, with many requiring multiple surgical interventions. Accurate diagnosis, particularly via exercising endoscopy, is key, as many disorders only become apparent during physical exercise.

Tieback (prosthetic laryngoplasty) is the most common wind surgery but carries risks such as aspiration, pneumonia and swallowing dysfunction, despite efforts to improve surgical techniques. Newer techniques, like standing tiebacks and improved implants (e.g., titanium buttons, reinforced screws), aim to reduce complications and enhance results.

Other surgeries like Hobday (vocal fold removal via laser) were also discussed, emphasising the delicate nature of airway surgeries and the ongoing challenge to balance treatment effectiveness against risks and complications in our racehorses.

For DDSP, tie-forward surgery, which mimics natural muscle action to restore laryngeal position, has shown positive results, while thermocautery remains controversial. Epiglottic entrapment can now be safely corrected in standing horses using lasers or scissors. Emerging therapies include laryngeal reinnervation and dynamic neuroprosthesis to restore muscle function, as well as vocal fold filling to reduce aspiration pressure.

Collagen cross-linking is also under investigation as a less invasive method for soft palate stiffening. Barnett concludes, precise diagnosis and tailored interventions are crucial for optimal results in treating upper airway disorders in racehorses. These advances reflect a growing push for safer, more effective airway interventions in the racehorse.

Barnett then moved onto discussing the critical role of exercise endoscopy in diagnosing upper airway dysfunction in Thoroughbreds, highlighting the limitations of resting endoscopy. While useful for detecting conditions like total RLN, epiglottic entrapment, or arytenoid chondritis, resting scopes often miss dynamic issues such as soft palate disorders and vocal fold collapse.

Recent developments in overground endoscopy which are battery-powered and rider-compatible, allow evaluation during real time exercise, providing accurate and practical diagnosis. This method has become the preferred standard, especially for assessing palatal instability and early RLN.

Clinical signs such as respiratory noise, poor performance, or sudden stops may indicate airway dysfunction, but accurate diagnosis requires proper exercise testing with horses cantering or galloping while synchronising breaths per stride. Additional tools like laryngeal ultrasonography aid diagnosis and planning of treatment.

Barnett cautioned against performing airway surgery without thorough diagnostics, as multiple simultaneous conditions can exist, and treatments must be carefully targeted to improve outcomes. Around 25% of Thoroughbreds show clinical RLN, reinforcing the need for tailored, evidence-based treatment plans to support both welfare and performance.

Laryngeal surgeries - the evolution of research and engineering of the tie back and nerve graft

Dr Fabrice Rossignol, of Grosbois/Chantilly Equine Clinic discussed laryngeal surgeries, focussing on the evolution of research and engineering of the tie back and nerve graft. Rossignol’s specialist clinic is at the forefront of treating recurrent laryngeal neuropathy (RLN).

The condition is often linked to degeneration of the recurrent laryngeal nerve, affecting the cricoarytenoideus dorsalis (CAD) muscle, which is critical for opening the airway during exercise. Rossignol explains that this muscle contains few fatigue-resistant fibres, making it vulnerable to atrophy. Even minor narrowing of the airway significantly increases resistance, due to the exponential pressure effects described by Poiseuille’s law.

Diagnosis involves treadmill endoscopy and ultrasonography (caudal view of swallowing can be particularly useful) to assess dynamic airway collapse and muscle atrophy. Treatment is tailored to severity; advanced cases may require a tieback (laryngoplasty) using synthetic prostheses to partially open the arytenoid cartilage, though this risks complications like coughing. Newer techniques aim to restore function rather than replace it. One such innovation combines traditional tieback surgery with nerve grafting from the spinal accessory nerve, which activates during inspiration and contains fatigue-resistant fibres.

This hybrid approach improves airway opening and reduces side effects. Standing surgery under sedation allows more precise suture placement, minimising anaesthetic risk. Emerging technologies like 3D-printed implants and titanium screw anchors further enhance outcomes. Rossignol echoes Barnett’s earlier advice, that early intervention and careful case selection remain key to success.

Dr Rossignol continued on to discuss what and how we, as a racing industry, can learn from other disciplines.

Recent research in trotters and sport horses highlights how neck flexion contributes to dorsal and lateral pharyngeal collapse, likely due to nerve inflammation affecting muscles such as the stylopharyngeus. Nasal obstruction, including alar fold collapse and nasal muscle paralysis, also play a role in compromised airflow. Treatment options now include alar fold resection, nasal fenestration (widening), and innovative approaches like titanium mesh implants to replace lost muscular function.

Dr Rossignol explains that high-speed treadmill testing has proven critical in diagnosing dynamic airway conditions, while a multidisciplinary approach involving vets, trainers and farriers enhances management strategies. Use of nasal dilation devices, such as nasal strips, remains restricted under many jurisdictions' rules of racing.

It is clear that Rossignol champions cross-disciplinary learning, working with trotter trainers over decades has yielded practical insights, such as shoe removal to enhance performance. The methodical, detail-driven tack and equipment adjustments made in trotting disciplines provide valuable lessons in optimising performance.

Dr Rossignol also shares advances in surgical techniques, including refined approaches to epiglottic entrapment, emphasising the importance of collaborative care. Cross-disciplinary exchange continues to inform diagnosis, treatment and rehabilitation, enriching equine sports medicine and improving outcomes across disciplines.

An update on wind surgeries: what's new?

To conclude the lectures on wind ops, Mark Johnston, Dr Rossignol and Tim Barnett took to the floor to field audience questions. The discussion focused on recurrent laryngeal hemiplegia (RLN) in horses, highlighting its probable hereditary component but unclear linking between particular genes. Experts note the complexity of breeding influences and caution against oversimplifying genetic causes, as RLN will most likely be linked with other traits.

Surgery helps individual horses but may skew breeding populations, as generally only the more expensive stallions receive treatment. Disclosure of surgeries before breeding is debated but difficult to enforce. Non-surgical solutions like resistance masks are emerging but their impact on reducing surgery isn’t yet clear. Overall, understanding and managing RLN’s genetics and treatment remain challenging and unresolved.

Early diagnosis of recurrent RLN relies on ultrasonography to detect early muscle atrophy; surgery is recommended promptly to prevent irreversible damage. In contrast, dorsal displacement of the soft palate (DDSP) often stems from muscle fatigue, immaturity, or inflammation and is best treated medically with training and reinforcement until at least three years old. Surgery is a last resort if medical management fails.

Multiple surgeries can be ethical if done safely and explained clearly. Yearling wind testing is variable and challenging to interpret, complicating sales disclosures. The increase in buyers scoping foals’ pre-sale is seen as an invaluable and unpleasant practice due to solid evidence that a foal’s laryngeal physiology will and can change tremendously as they mature. Ongoing research explores novel therapies such as pacemakers and magnetic stimulation.

The practical management of tendon rehabilitation

There is no introduction needed for Mark Johnston, who kindly provided us with his insight on the practical management of tendon rehabilitation. A renowned trainer with decades of experience offered a pragmatic view on tendon injury rehabilitation in racehorses, challenging long-held optimism around recovery. Despite advancements in ultrasound imaging and a range of therapies, from anti-inflammatories to experimental interventions like carbon fibre implants, he is yet to witness a truly successful long-term return to peak performance in top-level racing following a diagnosed tendon injury.

While ultrasound provides valuable detail, he still relies most on visual and tactile assessment, particularly tendon profile and signs of ‘bowing,’ which he considers a critical turning point. In his experience, few flat horses make a full comeback; many may race again, but recurrent issues and shortened careers are the norm. Mark’s approach is rooted in realism: throw everything anti-inflammatory at the injury early, manage workload carefully, and temper expectations.

Long rest alone is rarely effective and controlled rehab and early, aggressive treatment are key. He notes that previous use of prophylactic anti-inflammatories post-race helped reduce injuries, and questions whether restrictions on racecourse treatments may hinder progress. Prevention, early detection, and practical management remain the trainer’s most reliable tools.

Tendon injuries in racehorses

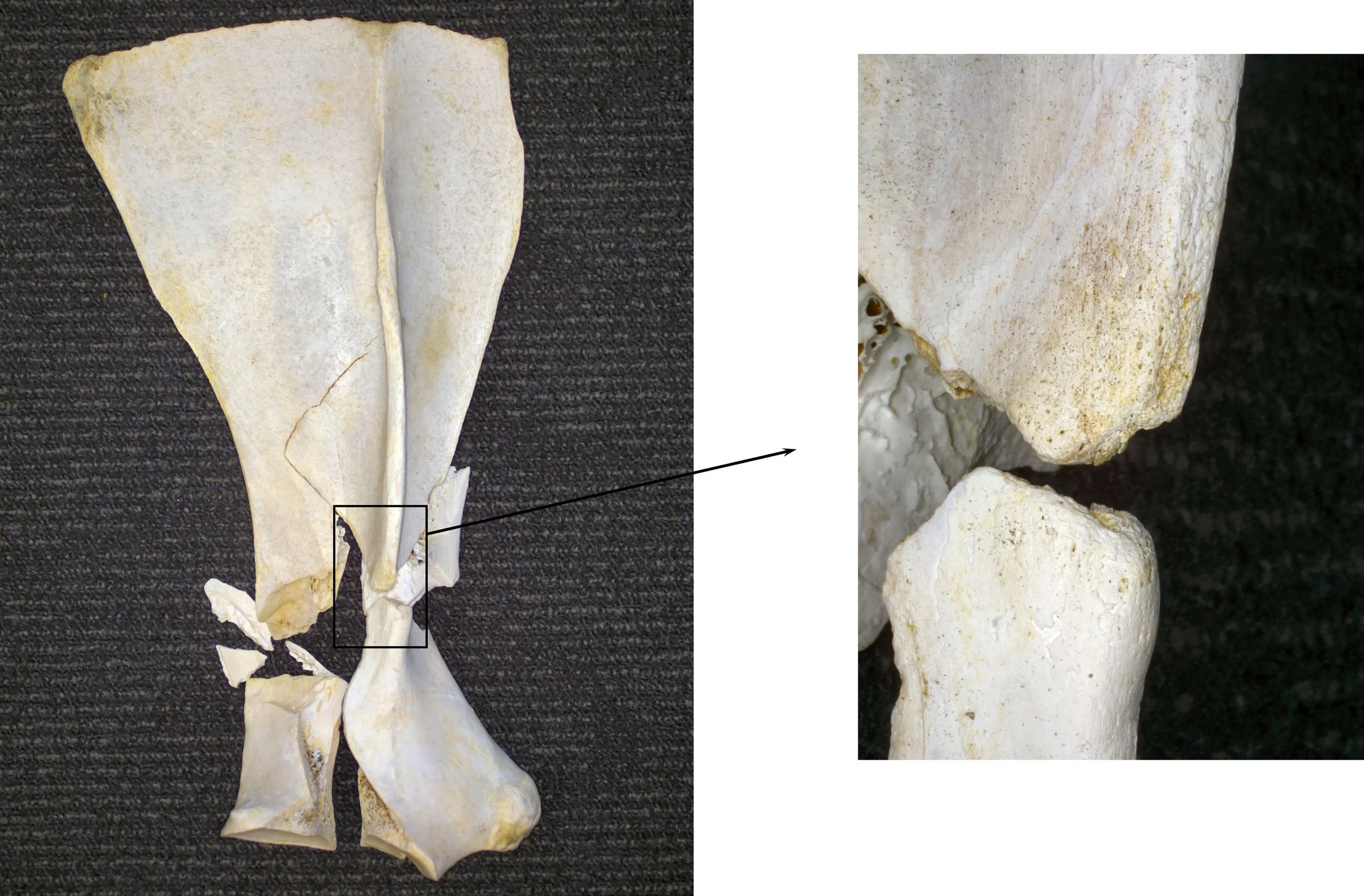

Professor Roger K.W. Smith FRCVS presented a detailed lecture on tendon injuries in racehorses, focusing on the superficial digital flexor tendon (SDFT) and the role of science in improving prevention and rehabilitation strategies. As a key structure for locomotion, the SDFT functions as an energy-storing spring but operates near its mechanical limits, especially in Thoroughbreds, making it prone to injury from accumulated loading rather than acute trauma.

Research shows that degeneration often precedes clinical injury, particularly within the interfascicular matrix (IFM), which loses elasticity with age and training. Tendon cells also become less responsive with age, impairing repair. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are implicated in post-exercise matrix degradation, further weakening the tendon.

Professor Smith emphasised prevention through training adjustments: avoiding hard ground, spacing out intense work, and ensuring sufficient recovery of, ideally 72 hours. Early detection is critical. Diagnostic tools such as ultrasound, Doppler, and Ultrasound Tissue Characterization (UTC) can identify structural changes before injury becomes apparent.

When injury occurs, a prolonged, structured rehabilitation programme guided by regular imaging is essential. Biologic therapies like mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and platelet-rich plasma (PRP) are showing encouraging results, improving tendon structure and reducing re-injury rates. A personalised, biologically informed approach remains key to safeguarding tendon health in racehorses.

Tendinopathy - its causes, treatments and parallels between equine and human medicine

Lt. Col. Dr Tom Clack delivered a comprehensive lecture on tendinopathy, highlighting its causes, treatments, and parallels between equine and human medicine. Tendinopathy, a chronic overuse injury, follows a three-stage progression: reactive tendinopathy (early inflammation), tendon disrepair (structural change and neovascularisation), and degenerative tendinopathy (reduced symptoms but increased rupture risk).

Historically, eccentric loading exercises, which came about via human Achilles research, became the core treatment. Today, management is more tailored, focusing on biomechanics, load control, and personalised rehabilitation.

Diagnosis includes clinical evaluation and ultrasound, with advanced modalities like Shearwave elastography and UTC offering deeper insights into tendon integrity and healing.

Dr Clack advocated a multimodal treatment strategy: progressive loading, extracorporeal shockwave therapy (ESWT), and injectables such as corticosteroids (for short-term relief) and PRP, which supports healing through growth factors.

Crucially, he emphasised the value of Thoroughbred racehorses as models for human tendon injury. Their tendons endure similar high loads, and developments in imaging, PRP, and regenerative therapies in equine medicine are increasingly influencing human sports injury treatment.

Dr Clack echoed the importance of early detection, strategic recovery protocols, and ongoing collaboration between human and veterinary medicine to improve long-term outcomes in equine athletes.

Rehabilitating the equine athlete

We were then treated to a lecture by Veterinary surgeon Amelia MacArthur, who provided a grounded and insightful view on equine rehabilitation, shaped by her hands-on experience running a specialist rehabilitation yard in North Yorkshire. Based at the former training yard of Peter Beaumont, her facility includes a water treadmill, deep sand gallop, extensive hacking, and a quiet stable environment, all tailored to support recovery and performance conditioning.

It is clear that MacArthur advocates for a genuinely holistic approach, not rooted in fads, but in understanding the whole horse: injury history, temperament, conformation, previous management, and future athletic goals. Rehabilitation begins with controlled exercise, which is often hand-walking, though she acknowledges the safety challenges of managing fresh horses, advising use of protective gear and sedation when necessary. In-stable physiotherapy, such as weight-shifts and limb lifts, can supplement or replace walking early on.

She stresses that rehabilitation literature often lacks clarity, so individualised programs with regular reassessment, particularly ultrasound checks, are essential. Progressive loading, surface variation, and adapting treadmill use depending on injury type all help prevent reinjury. For tendon cases, treadmill work is delayed to avoid strain from reduced slip.

Crucially, MacArthur highlighted the impact of rider weight and balance, particularly for ex-racehorses, and the importance of body condition in supporting soundness. A striking case study showed how fat loss transformed a Highland pony’s tendon recovery and competitive ability.

Tendon injury; therapy and management

The final open floor discussion of the day took place between Mark Johnston, Professor Roger Smith, Dr Tom Clack and Amelia MacArthur. The topic of military-style training programmes running parallel with equine management were discussed, particularly in managing overuse injuries like stress fractures. Key strategies include load management and gradual conditioning over 4–8 week cycles. It was noted that today’s horses, like modern human recruits, can often lack natural conditioning, especially in the feet, increasing injury risk.

Prevention is focused on structured training that supports both tendon and bone development, particularly in young horses (yearlings), where tendons must adapt before bones are heavily loaded. Ground conditions and surface variation also play a complex role in musculoskeletal health.

Rehabilitation and pre-training approaches remain debated, but there's agreement that progressive, controlled exercise is essential. Tendon injuries, especially in flat racehorses, are notoriously hard to overcome. Advances in ultrasound and imaging, such as UTC and shockwave elastography offer new promise, though they come with high costs and technical demands.

National Hunt horses often return to competition successfully after injury, offering hope, but managing owner expectations remains key. Medication use, such as dexamethasone, is tightly regulated on racecourses to uphold integrity. Like elite human athletes, horses need carefully balanced workloads and rest to prevent chronic damage. While rehabilitation methods are improving, prevention remains the best strategy.

This year’s renewal of the Gerald Leigh Memorial Lectures was once again full to the brim with exciting new research and innovative thoughts from world leading experts. Attendees, all involved within various areas of the horseracing industry made for diverse and thought-provoking discussions.

The commonality amongst the lecturers and attendees alike was the undeniable commitment to ensuring the betterment of equine welfare in all avenues of bloodstock, racing and life after. Safe to say, all who attended are already looking forward to the 2026 lectures.

The work being done on the prevention of serious fractures in the racehorse

Fractures: are they inevitable or preventable?

The incidence of serious fractures in horses racing on the flat is low (around one case every one to two thousand starters); but when fractures occur the consequences are often severe for the horse and, sometimes, the jockey. Both the severity and the dramatic nature of these injuries cause a significant negative impact to everyone connected with the horse, as well as spectators.

The International Federation of Horseracing Authorities (IFHA) convened the Global Summit on Equine Safety and Technology at Woodbine Racecourse, Toronto, in June 2024, to focus on how current research into causes of racehorse fatalities on the course, including fractures, can be advanced and translated into action, to better understand the factors leading to fatalities and potentially mitigate them. At the meeting there were two workshops where specialist veterinary clinicians, pathologists and researchers came together to focus on Exercise Associated Sudden Death incidents and fractures.

1: Why do fractures occur?

While most fractures that affect racehorses on the flat appear to arise spontaneously, while the horse is racing, and in the absence of any obvious trauma, we now know that the majority are the consequence of structural fatigue, involving a process that started weeks or even months earlier. Just as a paper clip will break if it is repeatedly bent once too often, a bone will fracture if it is loaded recurrently beyond certain limits. Microscopic damage accumulates in the bone tissue until a small fissure develops, which can extend to a severe fracture if it is not detected and the horse continues to race.

The fatigue life of bone decreases exponentially as the magnitude of load on the bone during each loading cycle increases. Loads on the skeleton are directly related to the speed of exercise, work at a fast gallop causes fatigue damage at a rate many orders of magnitude greater than when the horse is exercised at slower speeds. Unfortunately, fatigue damage, and even formation of small fissures in the bone, often proceed without the horse showing any outward signs and so, historically, affected horses have often gone undetected until it is too late.

2: Are there any natural biological mechanisms that protect against fracture?

An ability to run fast has been of evolutionary benefit to horses by enabling them to escape predators. Humans have refined this characteristic in specific breeds, notably the Thoroughbred, through targeted breeding and training practices. The need for a horse to undertake a fast gallop in the wild is likely to be relatively infrequent and well-within the bounds that are likely to cause fatigue damage. Conversely, society’s expectations of racehorses, and the training imposed on them, place loads on the skeleton that may be excessive.

Some readers may be surprised to learn that bone is a remarkably “smart” tissue. It is so much more than the equivalent of the “concrete structural beam” laid down to support man-made structures. While bone is composed partly of minerals, it is still very much a living tissue, packed with blood vessels, nerves and cells. Furthermore, the cells are all physically interlinked through microscopic projections, and can communicate with each other through their interconnections. This biological network allows bone tissue to detect the effects of loads applied to the bone as whole, and to initiate a cellular response to model the bone structure if those loads change.

For instance, increase in the magnitude of prevailing loads (e.g. through increase in an animal’s weight or the introduction of high-speed work) will cause greater deformation of the bone and this will stimulate a process that results in the formation of additional bone mass and, if beneficial, subtle reshaping of the bone’s geometry. The bone will be stronger as a result and deform less for the given load. Conversely, if the prevailing loads decrease (e.g. during a period of rest) bone deformation is reduced, and bone may be removed through a process of resorption. This overall mechanism of remodelling is called “adaptation”. Bone adaptation facilitates the formation and maintenance of a skeleton that is continually fit for purpose, even as that purpose changes.

Beyond this, there are biological mechanisms that detect when a bone is damaged (e.g. small cracks develop) and will initiate repair. The restoration process involves removal of microscopic packets of bone tissue, including the damaged portion, and its replacement with fresh, healthy material. This process means that fatigue-related damage of bone can be resolved and, theoretically, that a bone can tolerate infinite cycles of load. However, the process of repair has been shown to be inhibited if the bone is still regularly subjected to cycles of high load (i.e. the horse remains in training) and it can also be overwhelmed if the rate of damage accumulation is too high.

3: Are fractures something that racing just has to live with or can we do something about them?

Applying the knowledge we have gained from research over the past forty years has already had an impact on reducing the risk of fractures in some situations, and there are good reasons for optimism that we will be able to prevent a much greater proportion of racing fractures in the future. For example, epidemiological studies can help to identify certain management practices and design features of racecourses associated with an increased risk of fracture and these can be modified.

The introduction of strict rules governing the validity of sale of a horse in a claiming race in some jurisdictions in the USA, depending on the health status of the horse immediately after the race, has had a significant impact on reducing the incidence of fractures. Over 300 potential risk factors have been examined and those found to have a significant association with fracture, modelled in numerous studies.